So, after the recent shootings, we have people once again screaming at each other over the legality of firearms. While debate over issues such as this are healthy, much of what gets thrown about is hyperbole and vitriol, and as such it is just typical stupid politics. As there is alot of shouting and many people whop think that they have well-thought out positions, when they are actually just having knee-jerk reactions covered up by barely coherent figleaf justifications, this annoys me...and if it were likely to lead to any real policy changes, they would probably be bad policy cased on emotional over-reaction and vitriol more than on actual facts.

Before I get into the meat of this entry, I want to tell you where I stand on this issue, so that you will understand my own interests and biases:

As a legal matter, the 2nd amendment is vague regarding actual gun rights. Yes, I know, you are certain that it states flat-out that the right to keep and bear arms must not be infrigned, or perhaps you are certain that it states that only a well-regulated militia should keep arms. Go read the damn thing - see the placement of that comma? That actually makes the phrasing vague. And in legal terms, the phrasing being vague means that the law itself is vague. Grow up and deal with the fact that interpreting the amendment is not a clear-cut matter. If you believe otherwise, then you are reading what you want the text to say, but not what it actually says.

However, I am one of those people who thinks that, in cases where phrasing is vague, the law should be interpreted in the way that people are given a greater degree of freedom vis-a-vis the law. So, I am of the opinion that the 2nd amendment should be read as allowing relatively broad gun ownership rights to the average citizen.

However, whatever my view of the law, I am myself not a lover of guns. I do not own guns. I do not like guns. I will not have a gun brought into my home. Unlike many people involved in this shouting match, I am mature enough to understand that people can have a legal right to something without me personally wanting to exercise that right.

While I strongly dislike guns, I do like many people who themselves like guns. I have known enough gun owners to realize that the notion of the "gun nut" is mostly fiction. Yeah, there are a few scary firearm owners out there, but my experience is that they are abnormalities and, frankly, the gun owners that I know do not scare me. They are generally responsible, safety-minded, and not a threat to me or anyone else.

So, my position: I dislike guns, but they should be legal, most gun owners don't bother me and I even really respect the safety-mindedness of most of them, and I am of the mind that most of the vitriol regarding gun control is political nonsense either pushing or opposing an agenda that is calculated to motivate voters rather than forward policy.

Okay, on with the entry...

Much of what the people in favor of weapon bans worry about is dubious or just plain wrong (in other words, it's bullshit): firearm violence is actually much less common than it was even as recently as the 1990s, despite a growing population, and most of what is committed is gang-related and not likely amenable to control using standard gun control measures; most gun violence is committed not with "assault weapons*" but with hand guns; when one compares rates of gun ownership to number of gun homicides, while there is a relationship between the number of firearms and the number of homicides, it isn't exactly the tightest correlation around; events in Europe have demonstrated that mass-killings are not unique to the United States; and when one looks at the numbers and the spread of firearm violence around the world, the inescapable conclusion is that these massacre shootings are both abberations away from trends involving firearms and are not unique to the U.S., though that goes against much popular opinion.

At the same time, people who are opposed to gun control measures are known to spew their own particular brand of bullshit. While there are incidents where the possession of firearms by the general public has assisted in ending violent attacks, there are many cases where the use of a gun against an assailant is most likely to have increased the body count (consider the logistics of people firing back at the Aurora, Colorado gunman in a crowded theater - the body count can only have gone up if people fired back), so the usual claim of "more guns = less deaths" isn't necessarilly true; while the precise ratio is open to debate, the data does show that firearms in the home are far more likely to result in death or injury due to mis-use or accident than to be successfully used in self defense (indeed, I myself once had a gun pulled on me by a family member who mistakenly thought that I was a burgular - and for the record, I was in a bedroom with the door closed and a light on light on and not skulking about a dark house sneaking up on people); and comparisons often used in rhetoric championed by the NRA is often completely absurd; for example, comparing gun deaths to automobile deaths - an automobile is built for transportation, and as dangerous as it can be, its principle purpose is to transport people and goods; a gun is a weapon, it is designed specifically to kill or injure either a human or an animal [in the case of hunting rifles] - these are not at all the same things and comparing them is mind-bendingly stupid. Similarly, the phrase "guns don't kill, people do" is as sophomoric and half-witted a slogan as one can have - the tools available influence people's decisions, and that guns make killing easier and more prone to quick impulses can not be ignored. The tools influence the people just as people use the tools.

But here's the rub. Both sides are partially wrong, but tend to act as if they are entirely right. The end result, both have taken up office space in a house of cards. Most people probably don't have a particularly strong view on this subject, but of those who do, there is a polarization into increasingly irrational camps, and advocation of positions that often make little sense.

If there is going to be any meaningful steps taken towards curbing gun violence, they will need to account for the legal realities of gun ownership within the United States, they will have to account for the culture of gun ownership, they will have to account for the real facts of self defense vs. accidental gun deaths, and they will have to be based on the real nature of gun violence - both the truth regarding it's prevalence (ignoring media panic) and regarding how guns play into it (ignoring the NRA's slogans).

Until and unless we are able to ignore the noise, admit that "my side" can by wrong, and look at the truth of the matter, we shouldn't expect to make any progress regarding gun violence.

*The more time I spend around people who are into guns, the more I come to realize that the term "assault rifle" or "assault weapon" means very little in a technical sense, and as such isn't very useful in actually understanding the issues.

Subtitle

The Not Quite Adventures of a Professional Archaeologist and Aspiring Curmudgeon

Tuesday, August 28, 2012

Thursday, August 23, 2012

Morro Rock

Morro Rock, at the mouth of Morro Bay, is a large chunk of volcanic rock, over 20 million years old, a result of long-extinct volcanoes along the California coast. It is one of the Nine Sisters - a chain of similar large volcanic peaks located in San Luis Obispo County - and may represent locations where the continental plate moved over a volcanic hotspot over the eons.

Of interest to me, Morro Rock is often held to be a sacred place to both Chumsh and Salinan peoples, and given its looming presence at the mouth of Morro Bay, it would be surprising if it weren't. Unfortunately, like many elements of Native Californian Religion, the importance of Morro Rock is largely preserved through an oral history that has been damaged due to the impacts of Spanish colonization and the post-Gold Rush Americanization of the region.

When I was in graduate school, I would pass by Morro Bay and see Morro Rock whenever I drove north to visit family in Modesto. I always thought that I should stop off some day and have a look, but never did.

Last Saturday, I had the day to myself, and decided to take a drive out to the area, stopping to spend a good part of the day in the town of Morro Bay itself. The rock, which was once essentially an island off-shore, is now reachable via an artificial sandbar and walkway. I drove out and parked next to it, and spent some time walking around the 1/3 or so of the rock that has walkways. Climbing on the rock is prohibited, as it is a bird sanctuary, and given that large slabs of rock often fall off of it's nearly vertical surfaces, climbing on it is not particularly safe, anyway.

Given the history of the area, it was appropriate that, as I drove by the narrow estuary that is Morro Bay itself, I saw a strange canoe in the water. My first thought was "hey, that looks like a Tomol" the unique Chumash plank canoe. As I drove, I came to the boat launch, and saw a sign indicating that there was a meeting of Chumash elders that day, meaning that I had, in fact, seen a Tomol.

This was particularly exciting for me as the Tomol has long been prominent in my mind because there are strong arguments that the advent of the Tomol canoe allowed frequent trips across the Santa Barbara Channel, allowing some rather important trade routes to be more reliably opened, sparking the growth of Chumash culture after AD 1000. I had seen the canoes hanging in museums and in illustrations, but never in use - but here were two of them being paddled around the bay by a group of Chumash elders. And here I was, perfect timing, with a camera in my hand.

Anyway, I am very happy that I finally decided to visit Morro Bay. What's more, I discovered that it is only a 2-hour drive from home (for some reason, I had always thought it was a longer drive), which means that getting out to the beach for a day trip is going to become more feasible for me.

Of interest to me, Morro Rock is often held to be a sacred place to both Chumsh and Salinan peoples, and given its looming presence at the mouth of Morro Bay, it would be surprising if it weren't. Unfortunately, like many elements of Native Californian Religion, the importance of Morro Rock is largely preserved through an oral history that has been damaged due to the impacts of Spanish colonization and the post-Gold Rush Americanization of the region.

When I was in graduate school, I would pass by Morro Bay and see Morro Rock whenever I drove north to visit family in Modesto. I always thought that I should stop off some day and have a look, but never did.

Last Saturday, I had the day to myself, and decided to take a drive out to the area, stopping to spend a good part of the day in the town of Morro Bay itself. The rock, which was once essentially an island off-shore, is now reachable via an artificial sandbar and walkway. I drove out and parked next to it, and spent some time walking around the 1/3 or so of the rock that has walkways. Climbing on the rock is prohibited, as it is a bird sanctuary, and given that large slabs of rock often fall off of it's nearly vertical surfaces, climbing on it is not particularly safe, anyway.

Given the history of the area, it was appropriate that, as I drove by the narrow estuary that is Morro Bay itself, I saw a strange canoe in the water. My first thought was "hey, that looks like a Tomol" the unique Chumash plank canoe. As I drove, I came to the boat launch, and saw a sign indicating that there was a meeting of Chumash elders that day, meaning that I had, in fact, seen a Tomol.

This was particularly exciting for me as the Tomol has long been prominent in my mind because there are strong arguments that the advent of the Tomol canoe allowed frequent trips across the Santa Barbara Channel, allowing some rather important trade routes to be more reliably opened, sparking the growth of Chumash culture after AD 1000. I had seen the canoes hanging in museums and in illustrations, but never in use - but here were two of them being paddled around the bay by a group of Chumash elders. And here I was, perfect timing, with a camera in my hand.

Anyway, I am very happy that I finally decided to visit Morro Bay. What's more, I discovered that it is only a 2-hour drive from home (for some reason, I had always thought it was a longer drive), which means that getting out to the beach for a day trip is going to become more feasible for me.

Tuesday, August 21, 2012

Science Process and Scientific Literacy

A common theme on this blog is irritation with the scientific illiteracy of much of the public. This is, it needs to be noted, different from a lack of educational achievement. While it is popular to divide the world into uneducated cretins and enlightened college graduates, this is complete bullshit. While certain forms of anti-scientific thinking are popular among those without degrees, things such as vaccine denial, hysteria over GMOs, and belief in bogus "energy healing" are extremely common among people with degrees.

In fact, my own experience is that those with degrees tend to be far more intractable in their false beliefs in large part because they have degrees. I have lost count of the number of times that I have had a conversation with someone who was spouting pseudo-scientific nonsense and had them respond finally with "well, I earned a degree from Stanford [or another major university], so clearly I'm smart enough to understand this!"

A degree from Stanford, or anywhere else, in literature or history does not make one knowledgeable about biology, medicine, or physics. Certainly, someone with such a degree can become knowledgeable about these subjects, but to rely on the fact that you have a degree and not on training on the subject in question is a sign of sloppy thinking.

Most of the time, people are simply accepting whatever is convenient for their social and political views, and ignoring any disconfirming data. So, people on the political right are perfectly willing to accept marginal and poorly done studies that conclude that there is doubt about climate change contrary to the general scientific consensus, but people on the political left are willing to accept equally dubious studies that allege harm from GMO crops; people on the social right are willing to buy all manner of nonsense about the alleged harms that homosexuals do to their families, but people on the social left are only too ready to accept dubious studies concerning the role of self esteem in crime.

Part of the problem is, I think, that there is a tendency to equate scientific literacy with acceptance of certain conclusions, a scientifically literate person is one who accepts that evolution occurred, to use one example. In truth, scientific literacy is about having a knowledge of the methods of science. Importantly, it is about knowing the parameters under which scientific knowledge is generated.

Let's take the example of the study by Andrew Wakefield that is used to make claims about a link between vaccines and autism. Many people either accepted it because it gelled with their social and political views (medicine bad, big pharma evil) or rejected it because it clashed with their views (vaccines are part of the progress of mankind!). Very few people who hold a strong view on it have actually read it.

I did read it. When I read it, I, like everyone else, was unaware that Wakefield had falsified data or tweaked his results. But I was struck by two things: 1) the causal mechanism that he suggested, wherein the thimerisol in the vaccine caused inflamation int he digestive tract that allowed infection leading to autism, didn't sound plausible. However, I am not a medical doctor and am aware that there may be something to this that I simply didn't understand (this recognizing of one's own limits in knowledge is an important part of scientific literacy). 2) The sample size was small, totaling 12 children. A small sample size is useful in trying to prove the plausibility of a basic concept, but is insufficient for actually proving anything medical because of the high odds of random chance interfering with a sample size that small.

So, after reading it, I went away thinking that it sounded implausible, but that I didn't know enough about the subject to judge that too strongly, and that the sample size was small and larger scale studies would be needed to find a link between vaccines and autism with any confidence. In other words, my own scientific literacy pointed to the problems with the study, but prevented me from ignoring it outright until such time as further data was generated. I continued to get vaccinations myself, and encouraged people with children to get them, as the general scientific consensus was still in favor of them, but I was open to the possibility that this might be wrong.

In time, large scale studies were performed, and they showed that there is no link between vaccines and autism, and Wakefield has since been revealed as an outright fraud. However, by that time, numerous people had jumped on the bandwagon of a hypothesis supported by a dubious small-scale study, leading to the resurgence of numerous nearly eradicated (and in some cases deadly) illnesses. A greater degree of scientific literacy would have cautioned people early on, and they would have considered the possibility of the study being accurate alongside the need for further study to test the hypothesis. Considering that children have been injured and killed because of vaccine denial, this is a case where a lack of scientific literacy resulted in very serious consequences.

Recently, studies have been published arguing that organic farming leads to healthier soil and that acupuncture is effective in dealing with pain. In both cases, people either jumped on board or rejected the claims based on their pre-existing beliefs, without ever actually looking into the contents of the studies themselves. The acupuncture study was riddled with problems (for a summary of it and similar studies, look here) that effectively eliminate it from consideration, while the organic farm studies are interesting and seem plausible, but tend to have small sample sizes and some methodological problems that decrease their ability to elucidate the issue. However, you would only know these things if you read the papers themselves and read the scientific discussions and criticisms of the papers, which most people don't. Most people go to Fox News or the Huffington Post and accept the summary from whichever source aligns with their social and political views without ever questioning the actual science itself. And, importantly, this is extremely common amongst educated people with degrees from well-respected universities.

Acceptance and rejection of many scientific claims often falls along political lines. Left-leaning individuals are more likely to accept that acupuncture is great, that organic farming improves soil, and that vaccines cause autism, all without seriously considering problems with and criticisms of the research; right-leaning individuals are more likely to embrace climate change denial and notions like intelligent design. Those with college degrees are most likely to be able to convince themselves that they are too smart to have been fooled and to be able to rationalize their conclusions, no matter whether they are debatable but possible (organic farming improves soil) or flat-out false (intelligent design). All are scientifically illiterate, and yet all think that they alone understand the world.

In sum: scientific literacy isn't about having the right knowledge, it's about having an understanding of how science works, which means knowing that one study doesn't "prove" anything, that multiple studies are necessary, the larger the scale the better, and that the criticisms of the studies are important - having certain base knowledge (the Earth orbits the sun, DNA codes many of our traits, etc.) is necessary and important but is no literacy in of itself. It's about knowing that you are not knowledgeable about any but a narrow range of topics, and that you have to accept that you may be wrong and that people ideologically opposed to you may be right on any given topic. It's about knowing that your educational background prepares you to evaluate information and ideas within the field that you studied, and does not make you more likely to be able to evaluate information outside of that field. And, importantly, being scientifically literate means understanding that the things that you wish to be true or that align with your beliefs may be false, and that you have to listen to criticism of ideas that you hold dear, for those criticisms might be correct.

In fact, my own experience is that those with degrees tend to be far more intractable in their false beliefs in large part because they have degrees. I have lost count of the number of times that I have had a conversation with someone who was spouting pseudo-scientific nonsense and had them respond finally with "well, I earned a degree from Stanford [or another major university], so clearly I'm smart enough to understand this!"

A degree from Stanford, or anywhere else, in literature or history does not make one knowledgeable about biology, medicine, or physics. Certainly, someone with such a degree can become knowledgeable about these subjects, but to rely on the fact that you have a degree and not on training on the subject in question is a sign of sloppy thinking.

Most of the time, people are simply accepting whatever is convenient for their social and political views, and ignoring any disconfirming data. So, people on the political right are perfectly willing to accept marginal and poorly done studies that conclude that there is doubt about climate change contrary to the general scientific consensus, but people on the political left are willing to accept equally dubious studies that allege harm from GMO crops; people on the social right are willing to buy all manner of nonsense about the alleged harms that homosexuals do to their families, but people on the social left are only too ready to accept dubious studies concerning the role of self esteem in crime.

Part of the problem is, I think, that there is a tendency to equate scientific literacy with acceptance of certain conclusions, a scientifically literate person is one who accepts that evolution occurred, to use one example. In truth, scientific literacy is about having a knowledge of the methods of science. Importantly, it is about knowing the parameters under which scientific knowledge is generated.

Let's take the example of the study by Andrew Wakefield that is used to make claims about a link between vaccines and autism. Many people either accepted it because it gelled with their social and political views (medicine bad, big pharma evil) or rejected it because it clashed with their views (vaccines are part of the progress of mankind!). Very few people who hold a strong view on it have actually read it.

I did read it. When I read it, I, like everyone else, was unaware that Wakefield had falsified data or tweaked his results. But I was struck by two things: 1) the causal mechanism that he suggested, wherein the thimerisol in the vaccine caused inflamation int he digestive tract that allowed infection leading to autism, didn't sound plausible. However, I am not a medical doctor and am aware that there may be something to this that I simply didn't understand (this recognizing of one's own limits in knowledge is an important part of scientific literacy). 2) The sample size was small, totaling 12 children. A small sample size is useful in trying to prove the plausibility of a basic concept, but is insufficient for actually proving anything medical because of the high odds of random chance interfering with a sample size that small.

So, after reading it, I went away thinking that it sounded implausible, but that I didn't know enough about the subject to judge that too strongly, and that the sample size was small and larger scale studies would be needed to find a link between vaccines and autism with any confidence. In other words, my own scientific literacy pointed to the problems with the study, but prevented me from ignoring it outright until such time as further data was generated. I continued to get vaccinations myself, and encouraged people with children to get them, as the general scientific consensus was still in favor of them, but I was open to the possibility that this might be wrong.

In time, large scale studies were performed, and they showed that there is no link between vaccines and autism, and Wakefield has since been revealed as an outright fraud. However, by that time, numerous people had jumped on the bandwagon of a hypothesis supported by a dubious small-scale study, leading to the resurgence of numerous nearly eradicated (and in some cases deadly) illnesses. A greater degree of scientific literacy would have cautioned people early on, and they would have considered the possibility of the study being accurate alongside the need for further study to test the hypothesis. Considering that children have been injured and killed because of vaccine denial, this is a case where a lack of scientific literacy resulted in very serious consequences.

Recently, studies have been published arguing that organic farming leads to healthier soil and that acupuncture is effective in dealing with pain. In both cases, people either jumped on board or rejected the claims based on their pre-existing beliefs, without ever actually looking into the contents of the studies themselves. The acupuncture study was riddled with problems (for a summary of it and similar studies, look here) that effectively eliminate it from consideration, while the organic farm studies are interesting and seem plausible, but tend to have small sample sizes and some methodological problems that decrease their ability to elucidate the issue. However, you would only know these things if you read the papers themselves and read the scientific discussions and criticisms of the papers, which most people don't. Most people go to Fox News or the Huffington Post and accept the summary from whichever source aligns with their social and political views without ever questioning the actual science itself. And, importantly, this is extremely common amongst educated people with degrees from well-respected universities.

Acceptance and rejection of many scientific claims often falls along political lines. Left-leaning individuals are more likely to accept that acupuncture is great, that organic farming improves soil, and that vaccines cause autism, all without seriously considering problems with and criticisms of the research; right-leaning individuals are more likely to embrace climate change denial and notions like intelligent design. Those with college degrees are most likely to be able to convince themselves that they are too smart to have been fooled and to be able to rationalize their conclusions, no matter whether they are debatable but possible (organic farming improves soil) or flat-out false (intelligent design). All are scientifically illiterate, and yet all think that they alone understand the world.

In sum: scientific literacy isn't about having the right knowledge, it's about having an understanding of how science works, which means knowing that one study doesn't "prove" anything, that multiple studies are necessary, the larger the scale the better, and that the criticisms of the studies are important - having certain base knowledge (the Earth orbits the sun, DNA codes many of our traits, etc.) is necessary and important but is no literacy in of itself. It's about knowing that you are not knowledgeable about any but a narrow range of topics, and that you have to accept that you may be wrong and that people ideologically opposed to you may be right on any given topic. It's about knowing that your educational background prepares you to evaluate information and ideas within the field that you studied, and does not make you more likely to be able to evaluate information outside of that field. And, importantly, being scientifically literate means understanding that the things that you wish to be true or that align with your beliefs may be false, and that you have to listen to criticism of ideas that you hold dear, for those criticisms might be correct.

Wednesday, August 15, 2012

Romanticizing the Egalitarians

As a graduate student, I worked as a teaching assistant as well as a lab instructor, and taught many a student the rudimentaries of anthropology and archaeology. A necessary part of the instruction is explaining the different types of social organization one is likely to encounter in the ethnographic and archaeological records.

And when you are dealing with alot of idealistic young college students, they tend to become quite enamored with "egalitarian" cultures...pretty much always without having a real understanding of what the term means.

And egalitarian culture is one where everybody is at about the same social level most of the time - someone may become a leader for a short time when their particular expertise or confidence is useful in a situation, only to give way to another leader under different circumstances. People follow not because someone is a chief or king or any other fixed hierarchical leader, but because that person is able to persuade others to follow them.

There are, of course, many different variations on egalitarian societies. In some, there may be some degree of formalized leadership, but it tends to be fluid and open to anyone who meets certain requirements (all men past the age of puberty, for example), in others there really are no recognition of leaders, just people who can persuade you to do things.

Naturally, my students would romanticize people who live(d) in these societies. There was a pervasive notion amongst the undergrads that people who lived in egalitarian societies were inherently more peaceful and led idyllic lives. One student even informed me that she felt moved to write a paper for another class that compared the (as she saw them) egalitarian and peaceful !Kung San of Africa with our current status-obsessed violent culture, and found us to be quite lacking.

I pointed out to this student that, according to the ethnography on which she was basing her views of the !Kung San, domestic violence was fairly common, and abject poverty the norm. In other words, there ain't no such thing as Utopia.

What my students never seemed to pick up on is that social organization tends to evolve in place (with the exception of those relatively unusual instances where it is successfully imposed from the outside...even in which cases it tends to e warped to fit local conditions and traditions). Egalitarian societies are not the product of gentle, enlightened souls who see a better way of organizing, they are the product of a system of resource procurement and use coupled with a low population density that allows such societies to exist without descending into chaos. Importantly, they only seem to work when you have a society in which there are a small enough number of people that everyone can both keep tabs on each other (to ensure that you are engaged in no wrong doing, and to make sure that you are not aggrandizing yourself) and equally share in the available resources. As soon as you have a large enough number of people packed into a small enough area, and accompanying resource stress, there is a need for organization in order to distribute what is needed to where it is needed. In other words, hierarchies, if they haven't formed already, will begin to form.

Now, with our ancestors, it's not clear which came first: did the population density/resource stress require hierarchies to develop, or did hierarchies develop and allow larger population densities to grow? It's an interesting question, but one that is rather beside the point as far as making judgements go. Once you have the number of people in the volume of space that occur in modern industrial and post-industrial nations, hierarchies are necessary.

That's not to say that the hierarchies always work well (they can be inefficient and ineffective) or that they are always nice to live in (ask a 19th century factory work about how much they enjoy life), but they are necessary to allow life to continue past a certain point in human cultural development. And we're not going to go back without killing off a huge portion of the global population.

If my students had recognized this, then they may have been able to start working towards what they really seemed to want: a society in which there is some degree of social equality even if organizational inequality is necessary - indeed, during the 19th and 20th centuries, progress was even made on this front. But as long as they romanticized these other cultures without recognizing both what allowed them to work, and the shortcomings of these societies, they were going to be dreamers without a viable cause.

And when you are dealing with alot of idealistic young college students, they tend to become quite enamored with "egalitarian" cultures...pretty much always without having a real understanding of what the term means.

And egalitarian culture is one where everybody is at about the same social level most of the time - someone may become a leader for a short time when their particular expertise or confidence is useful in a situation, only to give way to another leader under different circumstances. People follow not because someone is a chief or king or any other fixed hierarchical leader, but because that person is able to persuade others to follow them.

There are, of course, many different variations on egalitarian societies. In some, there may be some degree of formalized leadership, but it tends to be fluid and open to anyone who meets certain requirements (all men past the age of puberty, for example), in others there really are no recognition of leaders, just people who can persuade you to do things.

Naturally, my students would romanticize people who live(d) in these societies. There was a pervasive notion amongst the undergrads that people who lived in egalitarian societies were inherently more peaceful and led idyllic lives. One student even informed me that she felt moved to write a paper for another class that compared the (as she saw them) egalitarian and peaceful !Kung San of Africa with our current status-obsessed violent culture, and found us to be quite lacking.

I pointed out to this student that, according to the ethnography on which she was basing her views of the !Kung San, domestic violence was fairly common, and abject poverty the norm. In other words, there ain't no such thing as Utopia.

What my students never seemed to pick up on is that social organization tends to evolve in place (with the exception of those relatively unusual instances where it is successfully imposed from the outside...even in which cases it tends to e warped to fit local conditions and traditions). Egalitarian societies are not the product of gentle, enlightened souls who see a better way of organizing, they are the product of a system of resource procurement and use coupled with a low population density that allows such societies to exist without descending into chaos. Importantly, they only seem to work when you have a society in which there are a small enough number of people that everyone can both keep tabs on each other (to ensure that you are engaged in no wrong doing, and to make sure that you are not aggrandizing yourself) and equally share in the available resources. As soon as you have a large enough number of people packed into a small enough area, and accompanying resource stress, there is a need for organization in order to distribute what is needed to where it is needed. In other words, hierarchies, if they haven't formed already, will begin to form.

Now, with our ancestors, it's not clear which came first: did the population density/resource stress require hierarchies to develop, or did hierarchies develop and allow larger population densities to grow? It's an interesting question, but one that is rather beside the point as far as making judgements go. Once you have the number of people in the volume of space that occur in modern industrial and post-industrial nations, hierarchies are necessary.

That's not to say that the hierarchies always work well (they can be inefficient and ineffective) or that they are always nice to live in (ask a 19th century factory work about how much they enjoy life), but they are necessary to allow life to continue past a certain point in human cultural development. And we're not going to go back without killing off a huge portion of the global population.

If my students had recognized this, then they may have been able to start working towards what they really seemed to want: a society in which there is some degree of social equality even if organizational inequality is necessary - indeed, during the 19th and 20th centuries, progress was even made on this front. But as long as they romanticized these other cultures without recognizing both what allowed them to work, and the shortcomings of these societies, they were going to be dreamers without a viable cause.

Tuesday, August 14, 2012

Severing the Hand

Sometimes it seems like the people who work outside of California get all of the weird-ass sites.

So, in Egypt, pits have been found that contain the remains of hands. Specifically, the remains of severed right hands. In all, sixteen hands have been found, and some were located in areas where their burial pits in front of the throne room of a Hyksos* ruler by the tongue-twisting name of Seuserenre Khyan (original paper available here, summaries available here and here).

The Hyksos and Egyptians shared a practice of post-combat mutilation wherein a defeated opponent's right hand was severed (I have to wonder if, when a left-handed a opponent was defeated, a left hand would have been taken, but I don't know). This served a few functions: 1) it disabled an opponent, reducing or even destroying their ability to fight again; 2) it was a way of taking an easy tally of the number of opponents defeated (count up the hands, and you have your total); 3) in cases where a bounty was given for defeated enemies, it allowed proof of the defeat.

In this case, Egyptian records make it clear that the severed hands of defeated enemies were turned in to authorities for "the gold of valor" - that is, a bounty payment.

When I first read about this, my initial thought was "weird, a bunch of severed right hands! That's just bizarre!"

But, of course, it really isn't that bizarre. Post-combat mutilation, whether to the bodies of enemies, or to the still-living enemies, is fairly common, likely even the norm in complex, hierarchical societies that engage in organized warfare. The histories of Europe, Africa, Asia, and the Americas are replete with societies in which trophies were taken of the bodies of enemies, sometimes as proof of their defeat, sometimes for ritual purposes, sometimes for another reason altogether. And this isn't something relegated to our "savage" past. In the book Dead Mean Do Tell Tales, forensic anthropologist William Maples indicates that it was common enough for returning GIs to bring some rather grisly trophies back from the war, that when a skull that showed signs of being from a Japanese man was found, they initially assumed that it was the boiled-down remains of a decapitated Japanese soldier that had ended up in a U.S. soldier's grandchildren's attic.

The exact method used varies - sometimes it's a hand, sometimes it's an ear, or the head, or the scalp, or any number of other body parts. But the intention remains the same - mutilate the enemy, and take a sign of their defeat. Historically, this has backfired in some ways - there have been places where bounties offered for the removed body part have resulted in people taking the body part from other, innocent people, in order to collect - after all, who is to know whether the scalp came from an enemy soldier or your neighbor?

In addition to the reasons outlined above, I often wonder whether this prescribed mutilation might serve another purpose. We often fail to consider how the business of war screws with people's minds. Indeed, there has long been a tendency in the western militaries to deny that killing and being shot at has much of an effect on your psyche. But, throughout the world and throughout history, there have been practices geared towards directing the aggression and turmoil of soldiers. The Bible tells of Hebrew rituals that likely served to help warriors put their acts into perspective, and Roman and Greek sources talk of things that soldiers were and were not allowed to do in and after combat in order to keep them disciplined but also sane; and I rather suspect that if I did a reading of the war practices of other cultures throughout the world, I would see more of the same. In fact, when I read in the newspaper about U.S. soldiers in Iraq or Afghanistan involved in the mutilation of bodies, as much as I may be disgusted, I am not shocked - they are doing something that humans have since the onset of warfare, that it doesn't happen more often is a tribute to the level of discipline in modern militaries.

In this sense, I have to wonder if the prescribed mutilations might serve as a way of directing people's post-combat violent tendencies to a particular, predictable goal and preventing them from acting out in even more destructive ways. As distasteful as we may find these practices, I can not help but wonder if they served an important purpose. Regardless, archaeology has confirmed that Egypt was also home to this practice.

*Fun fact - many a biblical literalist, when confronted with the fact that there is no archaeological evidence for the Hebrews having been held captive in Egypt, will claim that there is plenty o' evidence, but that they were known as the Hyksos. This seems to come from a rather dubious claim made by the early historian Josephus Flavius, backed up by a misunderstanding of the etymology of the word Hyksos. Despite the fact that both archaeological and historical investigation have proven that the Hyksos were not the Hebrews - and, what's more, were perfectly capable of holding their own militarily, not the subjugated slaves of Exodus - this claim is still frequently made by Biblical apologists.

So, in Egypt, pits have been found that contain the remains of hands. Specifically, the remains of severed right hands. In all, sixteen hands have been found, and some were located in areas where their burial pits in front of the throne room of a Hyksos* ruler by the tongue-twisting name of Seuserenre Khyan (original paper available here, summaries available here and here).

The Hyksos and Egyptians shared a practice of post-combat mutilation wherein a defeated opponent's right hand was severed (I have to wonder if, when a left-handed a opponent was defeated, a left hand would have been taken, but I don't know). This served a few functions: 1) it disabled an opponent, reducing or even destroying their ability to fight again; 2) it was a way of taking an easy tally of the number of opponents defeated (count up the hands, and you have your total); 3) in cases where a bounty was given for defeated enemies, it allowed proof of the defeat.

In this case, Egyptian records make it clear that the severed hands of defeated enemies were turned in to authorities for "the gold of valor" - that is, a bounty payment.

When I first read about this, my initial thought was "weird, a bunch of severed right hands! That's just bizarre!"

But, of course, it really isn't that bizarre. Post-combat mutilation, whether to the bodies of enemies, or to the still-living enemies, is fairly common, likely even the norm in complex, hierarchical societies that engage in organized warfare. The histories of Europe, Africa, Asia, and the Americas are replete with societies in which trophies were taken of the bodies of enemies, sometimes as proof of their defeat, sometimes for ritual purposes, sometimes for another reason altogether. And this isn't something relegated to our "savage" past. In the book Dead Mean Do Tell Tales, forensic anthropologist William Maples indicates that it was common enough for returning GIs to bring some rather grisly trophies back from the war, that when a skull that showed signs of being from a Japanese man was found, they initially assumed that it was the boiled-down remains of a decapitated Japanese soldier that had ended up in a U.S. soldier's grandchildren's attic.

The exact method used varies - sometimes it's a hand, sometimes it's an ear, or the head, or the scalp, or any number of other body parts. But the intention remains the same - mutilate the enemy, and take a sign of their defeat. Historically, this has backfired in some ways - there have been places where bounties offered for the removed body part have resulted in people taking the body part from other, innocent people, in order to collect - after all, who is to know whether the scalp came from an enemy soldier or your neighbor?

In addition to the reasons outlined above, I often wonder whether this prescribed mutilation might serve another purpose. We often fail to consider how the business of war screws with people's minds. Indeed, there has long been a tendency in the western militaries to deny that killing and being shot at has much of an effect on your psyche. But, throughout the world and throughout history, there have been practices geared towards directing the aggression and turmoil of soldiers. The Bible tells of Hebrew rituals that likely served to help warriors put their acts into perspective, and Roman and Greek sources talk of things that soldiers were and were not allowed to do in and after combat in order to keep them disciplined but also sane; and I rather suspect that if I did a reading of the war practices of other cultures throughout the world, I would see more of the same. In fact, when I read in the newspaper about U.S. soldiers in Iraq or Afghanistan involved in the mutilation of bodies, as much as I may be disgusted, I am not shocked - they are doing something that humans have since the onset of warfare, that it doesn't happen more often is a tribute to the level of discipline in modern militaries.

In this sense, I have to wonder if the prescribed mutilations might serve as a way of directing people's post-combat violent tendencies to a particular, predictable goal and preventing them from acting out in even more destructive ways. As distasteful as we may find these practices, I can not help but wonder if they served an important purpose. Regardless, archaeology has confirmed that Egypt was also home to this practice.

*Fun fact - many a biblical literalist, when confronted with the fact that there is no archaeological evidence for the Hebrews having been held captive in Egypt, will claim that there is plenty o' evidence, but that they were known as the Hyksos. This seems to come from a rather dubious claim made by the early historian Josephus Flavius, backed up by a misunderstanding of the etymology of the word Hyksos. Despite the fact that both archaeological and historical investigation have proven that the Hyksos were not the Hebrews - and, what's more, were perfectly capable of holding their own militarily, not the subjugated slaves of Exodus - this claim is still frequently made by Biblical apologists.

Thursday, August 9, 2012

Movement Rock, Blandness, and Acceptance

I grew up in a neighborhood where a number of the other kids were only allowed to listen to "Christian Rock". As a kid, I was rather unimpressed with the music, but, then, I was also unimpressed with most of the pop music that I heard*, so I didn't think much of it. Years later, I worked with a woman whose music of choice was Christian Rock, and I listened again, and was further unimpressed. I didn't comment on my dislike until she asked me what I thought of it, and then I simply expressed that it wasn't to my taste. Her response was that I disliked it because of the "Christian message."

This wasn't true.

You see, I enjoy blues, I enjoy some jazz, I even enjoy some gospel music, and all of these (especially, and obviously, gospel music) have numerous entries that clearly espouse a Christian message. I may not be overly-fond of the message, and yet I often enjoy the music anyway. Why? Because it is good. The Christian messages in these songs are either expressions of the actual beliefs of the musicians or else expressions of ideas and concepts in play in the culture of the musicians. In other words, they were an inherent part of the musician's artistic intentions, and the music itself is often quite good - driven by the interests, emotions, and passions of the artists.

The Christian Rock that this woman and the kids in my childhood neighborhood listened to? It was essentially just over-produced pablum made to provide parents and teens with the means to listen to something that sounds vaguely like what was popular in the world at large without leaving their bubble and being challenged by outside ideas. It was the musical equivalent of religious Velveeta. What I had heard was less "Christian" music than the soundtrack to a niche marketing campaign.

I would, as time went on, encounter other music that gets grouped in with Christian Rock but which is produced by musicians who were trying to create their own music in their own voice, and was often quite good a result, regardless of my view of the "message". This sort of rock is solid music at worst and legitimate art at best. And yet it is rarely what people play when they play Christian rock, which I always found rather odd.

In the book Rapture Ready, Daniel Raddosh observes that while there is legitmately good art, in the form of music, fiction, visual art, etc., produced by evangelical Christians, much of what floods the Christian niche market (which is itself largely comprised of Evangelical Christians with a particular right-wing political bent) is of poor quality and of bland taste. He attributes this to the fact that much music, fiction, film, etc. is accepted based on its "message" rather than its merit, and as such, the producers who are able to produce the most simplistic, straightforward message are the ones who are easiest to spot as "safe."

More recently, I began to notice this same tendency in the atheist/skeptic communities. While these communities lack the financial backing to produce the sorts of market-friendly artists that the Evangelical Christian community possesses, and therefore the works produced in and for this community tend to remain quirkier and less "mainstream", there is nonetheless a definite tendency for people to grasp on to the message, rather than the work itself.

For example, I have often, both in person and online, been asked my opinion of George Hrab's music. Hrab is a professional funk drummer who also produces a wide range of music in many different styles, all of it with his own quirky, oddball twist. I have heard a few of his albums, and while I don't object to his music, with the exception of a few particular songs, it is not to my tastes. When I explain this, I typically receive a response of "but he's providing a good, skeptical message in his song lyrics!" Yes, yes he is...but that I agree with his message doesn't mean that I enjoy the music itself. In fact, there are times when the message actually hurts the music by using it as a ham-fisted vehicle for delivering a secular sermon.

Now, there are many people that I have met who legitimately like his music, and I say more power to them. But there is a definite undercurrent of people in these movements who listen to him because of "the message" rather than because they like his music.

Similarly, horror and science-fiction writer Scott Siegler writes stories based, as much as possible, and either real current science and technology, or on reasonable extrapolations thereof. As a result, he has gained a following amongst the skeptic/atheist community for his "realistic horror" stories (that is, stories that gain horror from potential real events, and not from supernatural nonsense). I have read one of his novels, and tried to read two others. While I can see the pulpy appeal of them, they are not for me. But, again, he is someone who is often held up for promoting a secular, materialist worldview in his writing. But, if I am reading a horror novel, I am doing so for entertainment, and if I am not entertained, I don't care what worldview the author is promoting.

And yet, people with whom I communicate in these communities routinely express disbelief that I would "fail to support a secular author."

Evangelical Christianity and the atheist and skeptic communities are, of course, not unique in this regard. I have encountered similar types of emphasis on message-over-substance amongst every group that could be considered a "movement" - from Libertarians to Greens, from hunters to vegans, etc. etc.

This shouldn't surprise us. That music, writing, visual art, and so on grow up out of these movements is to be expected. Given that these things have, since at least the early 20th century (even earlier depending on the art form) been essentially commercialized and badges of belonging, it makes sense that many producers would be accepted because they "send the right message" rather than because of their individual merits.

But damn, it is annoying.

*Yeah, I've always been a contrarian.

This wasn't true.

You see, I enjoy blues, I enjoy some jazz, I even enjoy some gospel music, and all of these (especially, and obviously, gospel music) have numerous entries that clearly espouse a Christian message. I may not be overly-fond of the message, and yet I often enjoy the music anyway. Why? Because it is good. The Christian messages in these songs are either expressions of the actual beliefs of the musicians or else expressions of ideas and concepts in play in the culture of the musicians. In other words, they were an inherent part of the musician's artistic intentions, and the music itself is often quite good - driven by the interests, emotions, and passions of the artists.

The Christian Rock that this woman and the kids in my childhood neighborhood listened to? It was essentially just over-produced pablum made to provide parents and teens with the means to listen to something that sounds vaguely like what was popular in the world at large without leaving their bubble and being challenged by outside ideas. It was the musical equivalent of religious Velveeta. What I had heard was less "Christian" music than the soundtrack to a niche marketing campaign.

I would, as time went on, encounter other music that gets grouped in with Christian Rock but which is produced by musicians who were trying to create their own music in their own voice, and was often quite good a result, regardless of my view of the "message". This sort of rock is solid music at worst and legitimate art at best. And yet it is rarely what people play when they play Christian rock, which I always found rather odd.

In the book Rapture Ready, Daniel Raddosh observes that while there is legitmately good art, in the form of music, fiction, visual art, etc., produced by evangelical Christians, much of what floods the Christian niche market (which is itself largely comprised of Evangelical Christians with a particular right-wing political bent) is of poor quality and of bland taste. He attributes this to the fact that much music, fiction, film, etc. is accepted based on its "message" rather than its merit, and as such, the producers who are able to produce the most simplistic, straightforward message are the ones who are easiest to spot as "safe."

More recently, I began to notice this same tendency in the atheist/skeptic communities. While these communities lack the financial backing to produce the sorts of market-friendly artists that the Evangelical Christian community possesses, and therefore the works produced in and for this community tend to remain quirkier and less "mainstream", there is nonetheless a definite tendency for people to grasp on to the message, rather than the work itself.

For example, I have often, both in person and online, been asked my opinion of George Hrab's music. Hrab is a professional funk drummer who also produces a wide range of music in many different styles, all of it with his own quirky, oddball twist. I have heard a few of his albums, and while I don't object to his music, with the exception of a few particular songs, it is not to my tastes. When I explain this, I typically receive a response of "but he's providing a good, skeptical message in his song lyrics!" Yes, yes he is...but that I agree with his message doesn't mean that I enjoy the music itself. In fact, there are times when the message actually hurts the music by using it as a ham-fisted vehicle for delivering a secular sermon.

Now, there are many people that I have met who legitimately like his music, and I say more power to them. But there is a definite undercurrent of people in these movements who listen to him because of "the message" rather than because they like his music.

Similarly, horror and science-fiction writer Scott Siegler writes stories based, as much as possible, and either real current science and technology, or on reasonable extrapolations thereof. As a result, he has gained a following amongst the skeptic/atheist community for his "realistic horror" stories (that is, stories that gain horror from potential real events, and not from supernatural nonsense). I have read one of his novels, and tried to read two others. While I can see the pulpy appeal of them, they are not for me. But, again, he is someone who is often held up for promoting a secular, materialist worldview in his writing. But, if I am reading a horror novel, I am doing so for entertainment, and if I am not entertained, I don't care what worldview the author is promoting.

And yet, people with whom I communicate in these communities routinely express disbelief that I would "fail to support a secular author."

Evangelical Christianity and the atheist and skeptic communities are, of course, not unique in this regard. I have encountered similar types of emphasis on message-over-substance amongst every group that could be considered a "movement" - from Libertarians to Greens, from hunters to vegans, etc. etc.

This shouldn't surprise us. That music, writing, visual art, and so on grow up out of these movements is to be expected. Given that these things have, since at least the early 20th century (even earlier depending on the art form) been essentially commercialized and badges of belonging, it makes sense that many producers would be accepted because they "send the right message" rather than because of their individual merits.

But damn, it is annoying.

*Yeah, I've always been a contrarian.

Tuesday, August 7, 2012

So You Want to be a Paranormal Investigator, Part 3

This is the third part of a series of posts geared towards how to think about research if you are someone who wants to be a paranormal investigator. Part 1 is here, and part 2 is here.

I had previously discussed issues with equipment and data-gathering. But there is a deeper problem, which I discussed briefly in the previous entries: Even if you get truly and clearly anomolous readings or weird sightings that shouldn't be there, what do they mean? Claims that temperature changes, eerie feelings, EMF fields, strange sounds, ionizing radiation, etc. are related to ghosts is always, without exception, based on assertions that are not backed up with any sort of bridging arguments linking the data to the conclusion. Unless you have a clear idea of what you are looking for and, even more importantly, why you are looking for it, any information gathered is absolutely meaningless. You need theory. Without theory, whatever it is that you are doing, it isn't research.

We need to be clear, though, and what, precisely, theory is. Contrary to what most of the public believes, theory is not synonymous with "wild ass guess", and contrary to what your elementary school teach taught you, it doesn't mean "a tested hypothesis that hasn't yet become a law."

Wikipedia actually has a pretty good definition in it's entry on the word:

In other words, theory is the set of observations, concepts, laws, and bridging arguments that provide a framework for exploring a concept. The germ theory of disease, for example, is the based around the concept that many illnesses are caused by microbiological agents, such as bacteria or viruses. Gravitational theory incorporates our observational data regarding gravity, and also provides testable hypotheses concerning what gravity actually is and precisely what causes it to work.

An important aspect of theory is that it changes over time. Gravitational theory was once limited to discussions of how gravity worked to make large objects attract each other. It was descriptive, and sought to describe things such as the motions of the planets, as well as objects falling to Earth. Over time, however, it grew, and now incorporates Einstein's general relativity, elements of particle physics, and so on. It began with observations of objects on Earth as well as the movement of objects through the sky. As more information was gathered, observations refined, and other physics questions probed and discoveries made, more and more information was added to gravitational theory. It grew from being descriptive (telling us how things behaved) to being predictive (telling us how they should behave under different conditions), and is increasingly explanatory (telling us not only how things have been observed to behave, and how we should anticipate them to behave, but also why they behave that way - what is gravity, exactly, anyway?).

All legitimately scientific fields build theory in this way: phenomenon are observed, the way in which they occur is more closely scrutinized and data gathered, the new data allows predictions to be made (that is, allows you to formulate hypotheses), which in turn allows you to further refine observations, ideas, and explanations. Theory allows you to keep track of the various parts of a field of study, keep them coherent, and keep them from getting lost or confused. Without theory, any attempt at research is dead in the water.

Within paranormal research, there is very little in the way of theory-building. This is due, in part, to the fact that there is little in the way of coherent data gathering. All of the ghost hunters running around with all of the infrared cameras and EMF meters available isn't going to produce anything worthwhile if there isn't some sort of structure to the matter. Why are EMF meters used? Why are infrared thermometers used? What are you really capturing on your digital voice recorder? Who knows? There's no reason to use any of this equipment, outside of "well, it's what those guys on TV do!" or "it's what the Shadowlands website says investigators should do."

Consider that physicists don't just run around with whatever pieces of equipment they can come up with and declare that their readings are indicative of, say, proton decay. No, they work out what a proton actually is based on a variety of different lines of evidence, how it's structured, and what the necessary results of its decay would be. THEN they use specific pieces of equipment that detect the particular things for which they are searching to see if their basic hypothesis is correct. Similarly, if you wish to do real, legitimate paranormal research, you must first choose the phenomenon that you wish to look into, then you must start collecting basic data, then you form research questions based on those observations, and then, and only then, do you start to work out which specialized tools are appropriate for what you are trying to discover.

So, if the paranormal phenomenon that you are interested in is ghosts (my own go-to, as shown by the fact that I have essentially geared this entire discussion towards it), you must first determine if there is even a phenomenon to be studied by collecting information from both accounts of alleged hauntings and from research on related fields - and you have to be very, very cautious in accounting for as many potential fields as possible. In the case of allegedly haunted places, you are looking at claims based on perceptions and people's memories of events, so you have to make sure that you are accounting for current work in the fields of perception and memory. Once you have used these fields to analyze the information that you have, you look for anomalies. You then set about trying to make some sort of sense of these anomalies - is there a pattern to them? Can they be explained by known phenomenon (for example, most "shadow people" sightings can be easily explained by a knowledge of how the eyes function)? If they can not be explained cleanly by known phenomenon, is there a known phenomenon that kind-of fits it, and if so, is the observation in question better explained by altering the explanations of the known phenomenon in a reasonable way (say, by appealing to other known phenomenon that may influence the first), or is it really something new? If it is something new, you once again gather information, looking for patterns, and seeing if there is anything that connects the data together. Over time, you will start to see links, you will start to piece things together. But it takes a long time, and it take alot of work, and it is something that is never going to be achieved by running around old houses using whatever random piece of equipment is in vogue with the ghost hunters this year. And, importantly, if you do this, while you may discover something new and interesting, if you are doing real research, then you absolutely must be open to the fact that you may find that exotic-seeming events may in fact be best explained through mundane phenomenon. If you discover that ghost sightings are best explained by neurology, or bad reactions to certain chemicals, or pet allergies...well, then, that is what you discovered, and a real researcher accepts this.

Rather than this, however, the current fields of paranormal investigation in general, and ghost hunting in particular, is a weird, cobbled-together Frankenstein's monster of unsubstantiated claims, faddish devotion to particular tools, and concepts borrowed from fantasy stories dressed up to sound scientific (psychokinetic energies, quantum energies leading to psychic phenomenon, inter-dimensional beings, etc.), but always essentially being assertions or suppositions without evidential backing, or even a real line of logic leading to them.

But it was not always this way. During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, real researchers began to look into questions regarding whether or not there is something more to us than our living bodies, whether or not there are things such as psychic powers, and whether reports of hauntings indicate and actual paranormal phenomenon or were simply quirks of human perception.

This ended for a number of reasons - some social, but many scientific. Initial tests on precognition and clairvoyance, for example, often seemed to show something, only to have later results demonstrate a regression to the mean, indicating that it was random chance at work. In other realms of paranromal research, investigation often revealed fraud or simple mistakes. Over time, without clear, favorable results, enthusiasm fizzled. After a time, the only people willing to engage in this work were the people who were perfectly willing to ignore negative results, and to focus instead on what looked like positive results when taken out of the broader context of the total results.

In other words, most of the people who stayed in the game were unwilling to follow where their results led, and would instead falsify or ignore data. In that sort of environment, it didn't take long for every claim to be considered at least viable, no matter how absurd. And so it is that we have paranormal researchers yammering on about "stone tapes" and "quantum potentiation leading to life after death" and "everyone having psychic abilities" despite the fact that none of these claims have been demonstrated, and many (basically, any claim involving the words "quantum" or "dimension") being so divorced from the actual, legitimate scientific uses of the key words that they are, literally, gibberish.

So, if you really want to do real paranormal research, this needs to change. There needs to be a concerted and honest effort to build up theory. Data needs to be recorded honestly and cleanly, negative results need to be acknowledged as being just as valuable as positive results, and you have to abandon all great edifices of pseudo-scientific gobbly-gook and start from basics.

And understand - when you approach professional scientific researchers, you will likely have to fight back their preconceptions about what you are doing. It's not that they are "closed-minded fools", it's that they have encountered many would-be paranormal investigators in the past, and none of them have ever been willing to do the hard work of real research, and have instead insisted that unsupported assertions be taken as fact, that an ignorance of data gathering methods was somehow superior to a clear and thought-out research methodology, and that data should be accepted only when it is favorable. In short, they will have crossed paths with people who are closed-minded and not willing to hear constructive criticism, and then been accused of being that themselves (I have encountered this myself, as has every researcher that I know). It may not be fair for them to view you with the cynicism that decades of this have earned, but it is human nature, and you have to be ready for it.

Also, understand, criticism is an important part of real research. Whenever I present results, I expect to be criticized, because there will always be something that I didn't think of but that should have been considered, or some piece of data of which I was unaware, or some other way to think of the results that never occurred to me. If you spend time reading the work of various paranormal investigators, you will hear that the "mainstream" scientist are criticizing them out of fear, or loathing, or a desire to "shut out undesired voices." Bullshit. Criticism is an important part of science. We criticize each other's work, because that is how we keep ourselves honest, and how we ensure that the best ideas, explanations, and data will eventually rise to the top (admittedly, sometimes it takes a while, but it gets there eventually). If you are being criticized, it means that you are being treated like a scientist, not that you are being shut down.

It will be difficult, it often won't be fun. But if you are serious about being a researcher/investigator, and not just being some goofy person who runs about with equipment that they don't actually understand, then you absolutely have to do this. And if you do this, then any positive results that you may get will be meaningful, and will be real contributions. If you don't do this, then your work will continue to be pseudo-science at best.

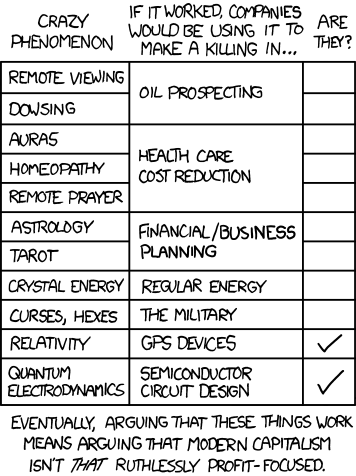

Good luck. P.S., if you are reading this and insisting that paranormal research has developed good, solid, theory, then I would point out that such theory regarding the sorts of things implied would allow for working applications of the concepts and powers studied. To that end, I will simply point you to this:

I had previously discussed issues with equipment and data-gathering. But there is a deeper problem, which I discussed briefly in the previous entries: Even if you get truly and clearly anomolous readings or weird sightings that shouldn't be there, what do they mean? Claims that temperature changes, eerie feelings, EMF fields, strange sounds, ionizing radiation, etc. are related to ghosts is always, without exception, based on assertions that are not backed up with any sort of bridging arguments linking the data to the conclusion. Unless you have a clear idea of what you are looking for and, even more importantly, why you are looking for it, any information gathered is absolutely meaningless. You need theory. Without theory, whatever it is that you are doing, it isn't research.

We need to be clear, though, and what, precisely, theory is. Contrary to what most of the public believes, theory is not synonymous with "wild ass guess", and contrary to what your elementary school teach taught you, it doesn't mean "a tested hypothesis that hasn't yet become a law."

Wikipedia actually has a pretty good definition in it's entry on the word:

In modern science, the term "theory" refers to scientific theories, a well-confirmed type of explanation of nature, made in a way consistent with scientific method, and fulfilling the criteria required by modern science. Such theories are described in such a way that any scientist in the field is in a position to understand and either provide empirical support ("verify") or empirically contradict ("falsify") it. Scientific theories are the most reliable, rigorous, and comprehensive form of scientific knowledge,[2] in contrast to more common uses of the word "theory" that imply that something is unproven or speculative.[3]Scientific theories are also distinguished from hypotheses, which are individual empirically testable conjectures, and scientific laws, which are descriptive accounts of how nature will behave under certain conditions

In other words, theory is the set of observations, concepts, laws, and bridging arguments that provide a framework for exploring a concept. The germ theory of disease, for example, is the based around the concept that many illnesses are caused by microbiological agents, such as bacteria or viruses. Gravitational theory incorporates our observational data regarding gravity, and also provides testable hypotheses concerning what gravity actually is and precisely what causes it to work.

An important aspect of theory is that it changes over time. Gravitational theory was once limited to discussions of how gravity worked to make large objects attract each other. It was descriptive, and sought to describe things such as the motions of the planets, as well as objects falling to Earth. Over time, however, it grew, and now incorporates Einstein's general relativity, elements of particle physics, and so on. It began with observations of objects on Earth as well as the movement of objects through the sky. As more information was gathered, observations refined, and other physics questions probed and discoveries made, more and more information was added to gravitational theory. It grew from being descriptive (telling us how things behaved) to being predictive (telling us how they should behave under different conditions), and is increasingly explanatory (telling us not only how things have been observed to behave, and how we should anticipate them to behave, but also why they behave that way - what is gravity, exactly, anyway?).

All legitimately scientific fields build theory in this way: phenomenon are observed, the way in which they occur is more closely scrutinized and data gathered, the new data allows predictions to be made (that is, allows you to formulate hypotheses), which in turn allows you to further refine observations, ideas, and explanations. Theory allows you to keep track of the various parts of a field of study, keep them coherent, and keep them from getting lost or confused. Without theory, any attempt at research is dead in the water.

Within paranormal research, there is very little in the way of theory-building. This is due, in part, to the fact that there is little in the way of coherent data gathering. All of the ghost hunters running around with all of the infrared cameras and EMF meters available isn't going to produce anything worthwhile if there isn't some sort of structure to the matter. Why are EMF meters used? Why are infrared thermometers used? What are you really capturing on your digital voice recorder? Who knows? There's no reason to use any of this equipment, outside of "well, it's what those guys on TV do!" or "it's what the Shadowlands website says investigators should do."

Consider that physicists don't just run around with whatever pieces of equipment they can come up with and declare that their readings are indicative of, say, proton decay. No, they work out what a proton actually is based on a variety of different lines of evidence, how it's structured, and what the necessary results of its decay would be. THEN they use specific pieces of equipment that detect the particular things for which they are searching to see if their basic hypothesis is correct. Similarly, if you wish to do real, legitimate paranormal research, you must first choose the phenomenon that you wish to look into, then you must start collecting basic data, then you form research questions based on those observations, and then, and only then, do you start to work out which specialized tools are appropriate for what you are trying to discover.