It seems that, whenever I encounter someone who is an advocate of some form of pseudo-archaeology, after I have exhaustively pointed out the flaws, inconsistencies, and made-up-shit that goes into their pet hypothesis, I am told something along the lines of "well, at least I (or the person who they are quoting) am trying to do something different with this information! THAT has value!"

If you are genuinely trying to do something new and innovative with old information, and trying to do it in such a way that you are not engaging in fabricating information, using special pleading to make your case, or in some other way being a dishonest bastard, then yes, trying to do something new has value.

The people who use this as the last-line defense for their pet hypothesis, though? Well, A) they are almost always just trying to maintain an older, stupid idea ("ancient astronauts," Biblical literalism, etc.) and aren't actually trying anything new, and B) they are pretty much always conflating "trying something new" with playing fast-and-loose with evidence and ignoring anything even vaguely approaching logic or honesty.

If you think I'm being overly harsh, then let's consider the fact that this explanation is pretty much only used in pseudo-science, and is not present in any other realm where people try to arrive at some sort of coherent explanation of events.

For example, in criminal investigations, you would rightfully dismiss someone as a nut if they insisted that a theft was committed by aliens, and then proceeded to "prove" this by making references to out-of-context information from unrelated crimes, pulling bits and pieces of conspiracy beliefs from pop culture, making up "facts", and ignoring relevant information from the actual crime scene. They would certainly be "doing something new" with the information...but that something new would not only not get you anywhere closer to solving the crime, it would, in fact, move you farther and farther away from the real solution. A person doing this would be immediately drummed out of the investigation and replaced with someone who was, you know, actually mentally competent.

And yet this same basic procedure - pulling out-of-context information from unrelated sites, pulling "facts" out of pop culture rather than data, making false claims about relevant sites, and often just making shit up - is the norm in pseudo-archaeology, and even people who are not directly involved in it often defend these practices by claiming that the pseudo-scholar is "trying to do something new" with the information.

Often, perhaps typically, implied under all of this is the notion that real archaeologists (or, as the pseudo-archaeologists often label us "establishment archaeologists - booo, hisssss, bad establishment!") aren't trying to find anything new. Sometimes it is flat out stated - there are many claims from the pseudo scholars that actual scholars are just trying to maintain some sort of "status quo", which reveals the true depth of the ignorance of the pseudo scholars - but at least as often it's just sort of implied, clearly there as an accusation, but covered up enough that the accuser can deny it if called on it.

The truth, however, is that we are working far harder than any of these twits. We are routinely trying to test and verify our methods and our results (see here for a summarized history of how archaeology has changed, or read this for a more thorough discussion). I have opened myself up to criticism by my professional colleagues for presenting papers that were not in-line with established models of past cultures, I have also found and publicized artifacts that are out-of-keeping with established cultural chronologies, and I have long supported archaeologists who work on the frontiers of what we think we know (for example, those working on pre-Clovis archaeology in North America). And I am not alone, some solitary warrior fighting against the "establishment" - every archaeologist that I know who presents papers or publishes their findings does similar things. Trying to "do something new" is what archaeologists do.

Now, it could be said that we should be better at communicating this to the general public. That is a valid criticism, and certainly one that I, and others try to address by keeping blogs, giving public lectures, appearing on podcasts, and so on. Some of us are lucky enough to be able to participate in radio and television, which is where most people get their information.

However, while we might do a better job of communicating our work and our findings, that in no way absolves the pseudo-archaeologists who distort, lie, and obfuscate. And, if you are someone who is going to claim that real archaeologists aren't "doing something new" then I offer you a challenge: When is the last time that you read an issue of National Geographic? Smithsonian Magazine? Or looked at professional journals such as American Antiquity? If you haven't done so lately, then you don't know what archaeologists are up to, and you sound as ignorant as you truly are when you imply that we aren't doing anything, or are simply supporting the "status quo."

Subtitle

The Not Quite Adventures of a Professional Archaeologist and Aspiring Curmudgeon

Showing posts with label Pseudo-Science. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Pseudo-Science. Show all posts

Wednesday, February 13, 2013

Monday, October 29, 2012

What's in a Name? Or, Why You Should be Cautious in Comparing Languages...

While driving out the the field the other day, one of the archaeologists with whom I am working asked what the linguistic connection was between Cachuma - a place name from Santa Barbara County - and Kuuchamaa - a similar-sounding place name from San Diego County.

I didn't know the origin of Kuuchamaa, but it is the native name for Tecate Peak, an important sacred mountain that is the spiritual center for the Kumeyaay peoples of southern California and northern Mexico. Having read up on it, I still haven't a clue as to what the word means, but it is the name of both the place, and of a culture hero - a wise and powerful shaman - said to have once lived in that place*. The translation of the word appears to be hard to come by, so I am at a bit of a loss.

Cachuma, however, is a bit easier. Cachuma is the English bastardization of the Spanish bastardization of the Inezeno Chumash word Aqitsumu, meaning "constant signal", which was the name of a village located in the Santa Ynez Valley, near the current location of Lake Cachuma.

So, while Cachuma and Kuuchamaa seem similar at first glance, one appears to be the actual Kumeyaay word, while the other is a rather tortured telephone game version of an Inezeno word. Now, there could still be some linguistic connection between them, but that seems somewhat unlikely, as Aqitsumu fits in perfectly well with the Chumash language family**, and Kuuchamaa, as far as I have been able to tell (though I am a bit shaky on this) seems to fit in well with the Kumeyaay language, a dialect of Diegeno, part of the Yuman language family. So, there is no reason to assume a connection, despite superficial similarities.

The words, though similar, refer to different types of things (a sacred mountain/person's name and a village), and there is no reason to assume that they would have similar meanings. What's more, the version of Aqitsumu that bears the most resemblance to the Kumeyaay word, Cachuma, is also the version that is most divorced from native pronunciation. Further, the names come from two unconnected languages.

There is, in short, no reason to think that these words are in any way connected, and some reason to think that they are not.

What is interesting about this is that there is no reason to assume a linguistic connection between two groups of people who were separated by only a few hundred miles of space for centuries. Pseudoscientific language comparisons are often employed by people who wish to show a connection between two completely unrelated groups of people. It is a favorite approach of those who see the ancient Isrealites landing int he Americas, the Celts taking over parts of the midwest, Medieval Japanese explorers settling Mexico, or Egyptians colonizing South America (yes, there are people who believe every one of these things).

The method is as follows:

Step 1: Find a few words (or sometimes even one) from two languages that have even a superficial similarity

Step 2: Claim that the link between these two populations is proven

Step 3: Ignore everyone who actually knows what they are talking about when they point out that you are a fool.

But, as illustrated, even in a case where two words are both used as placenames, sound extremely similar, and are from groups separated by only a few hundred miles, there is still reason to doubt a connection. Keep this in mind whenever your wacky neighbor claims that some vague language similarities prove that the native people of New Jersey were actually descended from a clan of Bavarian sausage-makers.

*Kuuchamaa appears to be a manifestation of a messianic religious concept that appeared throughout southern California either shortly before or around the time that the Spanish arrived. Whether the Kuuchamaa version of the story is the origin for the others, represents a merger of the messianic story with another older religious tradition, or else a spontaneous manifestation of a similar story, I do not know...nor does anyone else as far as I have been able to tell. It's neat that even after well over a century of research, we still have some mysteries like this to explore in California.

**Chumashan languages were, until recently, thought to be part of the Hokan language family, but that view has now been largely discredited. As a result, Chumash is an oddity in that it has no known related languages (similar in this respect to the Basque language of Spain) and exists as a linguistic island alone on the California coast. While this is speculative, some researchers have posited that Chumash may be the last version of the original Native Californian language family, as the other languages in California appear to have come in from elsewhere. While intriguing, this idea remains speculation until such time as physical or paleolinguistic evidence can be found to back it up.

I didn't know the origin of Kuuchamaa, but it is the native name for Tecate Peak, an important sacred mountain that is the spiritual center for the Kumeyaay peoples of southern California and northern Mexico. Having read up on it, I still haven't a clue as to what the word means, but it is the name of both the place, and of a culture hero - a wise and powerful shaman - said to have once lived in that place*. The translation of the word appears to be hard to come by, so I am at a bit of a loss.

Cachuma, however, is a bit easier. Cachuma is the English bastardization of the Spanish bastardization of the Inezeno Chumash word Aqitsumu, meaning "constant signal", which was the name of a village located in the Santa Ynez Valley, near the current location of Lake Cachuma.

So, while Cachuma and Kuuchamaa seem similar at first glance, one appears to be the actual Kumeyaay word, while the other is a rather tortured telephone game version of an Inezeno word. Now, there could still be some linguistic connection between them, but that seems somewhat unlikely, as Aqitsumu fits in perfectly well with the Chumash language family**, and Kuuchamaa, as far as I have been able to tell (though I am a bit shaky on this) seems to fit in well with the Kumeyaay language, a dialect of Diegeno, part of the Yuman language family. So, there is no reason to assume a connection, despite superficial similarities.

The words, though similar, refer to different types of things (a sacred mountain/person's name and a village), and there is no reason to assume that they would have similar meanings. What's more, the version of Aqitsumu that bears the most resemblance to the Kumeyaay word, Cachuma, is also the version that is most divorced from native pronunciation. Further, the names come from two unconnected languages.

There is, in short, no reason to think that these words are in any way connected, and some reason to think that they are not.

What is interesting about this is that there is no reason to assume a linguistic connection between two groups of people who were separated by only a few hundred miles of space for centuries. Pseudoscientific language comparisons are often employed by people who wish to show a connection between two completely unrelated groups of people. It is a favorite approach of those who see the ancient Isrealites landing int he Americas, the Celts taking over parts of the midwest, Medieval Japanese explorers settling Mexico, or Egyptians colonizing South America (yes, there are people who believe every one of these things).

The method is as follows:

Step 1: Find a few words (or sometimes even one) from two languages that have even a superficial similarity

Step 2: Claim that the link between these two populations is proven

Step 3: Ignore everyone who actually knows what they are talking about when they point out that you are a fool.

But, as illustrated, even in a case where two words are both used as placenames, sound extremely similar, and are from groups separated by only a few hundred miles, there is still reason to doubt a connection. Keep this in mind whenever your wacky neighbor claims that some vague language similarities prove that the native people of New Jersey were actually descended from a clan of Bavarian sausage-makers.

*Kuuchamaa appears to be a manifestation of a messianic religious concept that appeared throughout southern California either shortly before or around the time that the Spanish arrived. Whether the Kuuchamaa version of the story is the origin for the others, represents a merger of the messianic story with another older religious tradition, or else a spontaneous manifestation of a similar story, I do not know...nor does anyone else as far as I have been able to tell. It's neat that even after well over a century of research, we still have some mysteries like this to explore in California.

**Chumashan languages were, until recently, thought to be part of the Hokan language family, but that view has now been largely discredited. As a result, Chumash is an oddity in that it has no known related languages (similar in this respect to the Basque language of Spain) and exists as a linguistic island alone on the California coast. While this is speculative, some researchers have posited that Chumash may be the last version of the original Native Californian language family, as the other languages in California appear to have come in from elsewhere. While intriguing, this idea remains speculation until such time as physical or paleolinguistic evidence can be found to back it up.

Labels:

Anthropology,

Critical Thinking,

History,

Pseudo-Science

Tuesday, August 7, 2012

So You Want to be a Paranormal Investigator, Part 3

This is the third part of a series of posts geared towards how to think about research if you are someone who wants to be a paranormal investigator. Part 1 is here, and part 2 is here.

I had previously discussed issues with equipment and data-gathering. But there is a deeper problem, which I discussed briefly in the previous entries: Even if you get truly and clearly anomolous readings or weird sightings that shouldn't be there, what do they mean? Claims that temperature changes, eerie feelings, EMF fields, strange sounds, ionizing radiation, etc. are related to ghosts is always, without exception, based on assertions that are not backed up with any sort of bridging arguments linking the data to the conclusion. Unless you have a clear idea of what you are looking for and, even more importantly, why you are looking for it, any information gathered is absolutely meaningless. You need theory. Without theory, whatever it is that you are doing, it isn't research.

We need to be clear, though, and what, precisely, theory is. Contrary to what most of the public believes, theory is not synonymous with "wild ass guess", and contrary to what your elementary school teach taught you, it doesn't mean "a tested hypothesis that hasn't yet become a law."

Wikipedia actually has a pretty good definition in it's entry on the word:

In other words, theory is the set of observations, concepts, laws, and bridging arguments that provide a framework for exploring a concept. The germ theory of disease, for example, is the based around the concept that many illnesses are caused by microbiological agents, such as bacteria or viruses. Gravitational theory incorporates our observational data regarding gravity, and also provides testable hypotheses concerning what gravity actually is and precisely what causes it to work.

An important aspect of theory is that it changes over time. Gravitational theory was once limited to discussions of how gravity worked to make large objects attract each other. It was descriptive, and sought to describe things such as the motions of the planets, as well as objects falling to Earth. Over time, however, it grew, and now incorporates Einstein's general relativity, elements of particle physics, and so on. It began with observations of objects on Earth as well as the movement of objects through the sky. As more information was gathered, observations refined, and other physics questions probed and discoveries made, more and more information was added to gravitational theory. It grew from being descriptive (telling us how things behaved) to being predictive (telling us how they should behave under different conditions), and is increasingly explanatory (telling us not only how things have been observed to behave, and how we should anticipate them to behave, but also why they behave that way - what is gravity, exactly, anyway?).

All legitimately scientific fields build theory in this way: phenomenon are observed, the way in which they occur is more closely scrutinized and data gathered, the new data allows predictions to be made (that is, allows you to formulate hypotheses), which in turn allows you to further refine observations, ideas, and explanations. Theory allows you to keep track of the various parts of a field of study, keep them coherent, and keep them from getting lost or confused. Without theory, any attempt at research is dead in the water.

Within paranormal research, there is very little in the way of theory-building. This is due, in part, to the fact that there is little in the way of coherent data gathering. All of the ghost hunters running around with all of the infrared cameras and EMF meters available isn't going to produce anything worthwhile if there isn't some sort of structure to the matter. Why are EMF meters used? Why are infrared thermometers used? What are you really capturing on your digital voice recorder? Who knows? There's no reason to use any of this equipment, outside of "well, it's what those guys on TV do!" or "it's what the Shadowlands website says investigators should do."

Consider that physicists don't just run around with whatever pieces of equipment they can come up with and declare that their readings are indicative of, say, proton decay. No, they work out what a proton actually is based on a variety of different lines of evidence, how it's structured, and what the necessary results of its decay would be. THEN they use specific pieces of equipment that detect the particular things for which they are searching to see if their basic hypothesis is correct. Similarly, if you wish to do real, legitimate paranormal research, you must first choose the phenomenon that you wish to look into, then you must start collecting basic data, then you form research questions based on those observations, and then, and only then, do you start to work out which specialized tools are appropriate for what you are trying to discover.

So, if the paranormal phenomenon that you are interested in is ghosts (my own go-to, as shown by the fact that I have essentially geared this entire discussion towards it), you must first determine if there is even a phenomenon to be studied by collecting information from both accounts of alleged hauntings and from research on related fields - and you have to be very, very cautious in accounting for as many potential fields as possible. In the case of allegedly haunted places, you are looking at claims based on perceptions and people's memories of events, so you have to make sure that you are accounting for current work in the fields of perception and memory. Once you have used these fields to analyze the information that you have, you look for anomalies. You then set about trying to make some sort of sense of these anomalies - is there a pattern to them? Can they be explained by known phenomenon (for example, most "shadow people" sightings can be easily explained by a knowledge of how the eyes function)? If they can not be explained cleanly by known phenomenon, is there a known phenomenon that kind-of fits it, and if so, is the observation in question better explained by altering the explanations of the known phenomenon in a reasonable way (say, by appealing to other known phenomenon that may influence the first), or is it really something new? If it is something new, you once again gather information, looking for patterns, and seeing if there is anything that connects the data together. Over time, you will start to see links, you will start to piece things together. But it takes a long time, and it take alot of work, and it is something that is never going to be achieved by running around old houses using whatever random piece of equipment is in vogue with the ghost hunters this year. And, importantly, if you do this, while you may discover something new and interesting, if you are doing real research, then you absolutely must be open to the fact that you may find that exotic-seeming events may in fact be best explained through mundane phenomenon. If you discover that ghost sightings are best explained by neurology, or bad reactions to certain chemicals, or pet allergies...well, then, that is what you discovered, and a real researcher accepts this.

Rather than this, however, the current fields of paranormal investigation in general, and ghost hunting in particular, is a weird, cobbled-together Frankenstein's monster of unsubstantiated claims, faddish devotion to particular tools, and concepts borrowed from fantasy stories dressed up to sound scientific (psychokinetic energies, quantum energies leading to psychic phenomenon, inter-dimensional beings, etc.), but always essentially being assertions or suppositions without evidential backing, or even a real line of logic leading to them.

But it was not always this way. During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, real researchers began to look into questions regarding whether or not there is something more to us than our living bodies, whether or not there are things such as psychic powers, and whether reports of hauntings indicate and actual paranormal phenomenon or were simply quirks of human perception.

This ended for a number of reasons - some social, but many scientific. Initial tests on precognition and clairvoyance, for example, often seemed to show something, only to have later results demonstrate a regression to the mean, indicating that it was random chance at work. In other realms of paranromal research, investigation often revealed fraud or simple mistakes. Over time, without clear, favorable results, enthusiasm fizzled. After a time, the only people willing to engage in this work were the people who were perfectly willing to ignore negative results, and to focus instead on what looked like positive results when taken out of the broader context of the total results.

In other words, most of the people who stayed in the game were unwilling to follow where their results led, and would instead falsify or ignore data. In that sort of environment, it didn't take long for every claim to be considered at least viable, no matter how absurd. And so it is that we have paranormal researchers yammering on about "stone tapes" and "quantum potentiation leading to life after death" and "everyone having psychic abilities" despite the fact that none of these claims have been demonstrated, and many (basically, any claim involving the words "quantum" or "dimension") being so divorced from the actual, legitimate scientific uses of the key words that they are, literally, gibberish.

So, if you really want to do real paranormal research, this needs to change. There needs to be a concerted and honest effort to build up theory. Data needs to be recorded honestly and cleanly, negative results need to be acknowledged as being just as valuable as positive results, and you have to abandon all great edifices of pseudo-scientific gobbly-gook and start from basics.

And understand - when you approach professional scientific researchers, you will likely have to fight back their preconceptions about what you are doing. It's not that they are "closed-minded fools", it's that they have encountered many would-be paranormal investigators in the past, and none of them have ever been willing to do the hard work of real research, and have instead insisted that unsupported assertions be taken as fact, that an ignorance of data gathering methods was somehow superior to a clear and thought-out research methodology, and that data should be accepted only when it is favorable. In short, they will have crossed paths with people who are closed-minded and not willing to hear constructive criticism, and then been accused of being that themselves (I have encountered this myself, as has every researcher that I know). It may not be fair for them to view you with the cynicism that decades of this have earned, but it is human nature, and you have to be ready for it.

Also, understand, criticism is an important part of real research. Whenever I present results, I expect to be criticized, because there will always be something that I didn't think of but that should have been considered, or some piece of data of which I was unaware, or some other way to think of the results that never occurred to me. If you spend time reading the work of various paranormal investigators, you will hear that the "mainstream" scientist are criticizing them out of fear, or loathing, or a desire to "shut out undesired voices." Bullshit. Criticism is an important part of science. We criticize each other's work, because that is how we keep ourselves honest, and how we ensure that the best ideas, explanations, and data will eventually rise to the top (admittedly, sometimes it takes a while, but it gets there eventually). If you are being criticized, it means that you are being treated like a scientist, not that you are being shut down.

It will be difficult, it often won't be fun. But if you are serious about being a researcher/investigator, and not just being some goofy person who runs about with equipment that they don't actually understand, then you absolutely have to do this. And if you do this, then any positive results that you may get will be meaningful, and will be real contributions. If you don't do this, then your work will continue to be pseudo-science at best.

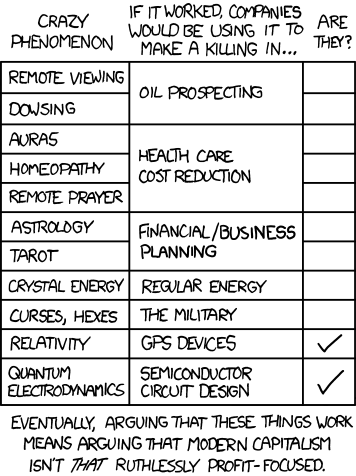

Good luck. P.S., if you are reading this and insisting that paranormal research has developed good, solid, theory, then I would point out that such theory regarding the sorts of things implied would allow for working applications of the concepts and powers studied. To that end, I will simply point you to this:

I had previously discussed issues with equipment and data-gathering. But there is a deeper problem, which I discussed briefly in the previous entries: Even if you get truly and clearly anomolous readings or weird sightings that shouldn't be there, what do they mean? Claims that temperature changes, eerie feelings, EMF fields, strange sounds, ionizing radiation, etc. are related to ghosts is always, without exception, based on assertions that are not backed up with any sort of bridging arguments linking the data to the conclusion. Unless you have a clear idea of what you are looking for and, even more importantly, why you are looking for it, any information gathered is absolutely meaningless. You need theory. Without theory, whatever it is that you are doing, it isn't research.

We need to be clear, though, and what, precisely, theory is. Contrary to what most of the public believes, theory is not synonymous with "wild ass guess", and contrary to what your elementary school teach taught you, it doesn't mean "a tested hypothesis that hasn't yet become a law."

Wikipedia actually has a pretty good definition in it's entry on the word:

In modern science, the term "theory" refers to scientific theories, a well-confirmed type of explanation of nature, made in a way consistent with scientific method, and fulfilling the criteria required by modern science. Such theories are described in such a way that any scientist in the field is in a position to understand and either provide empirical support ("verify") or empirically contradict ("falsify") it. Scientific theories are the most reliable, rigorous, and comprehensive form of scientific knowledge,[2] in contrast to more common uses of the word "theory" that imply that something is unproven or speculative.[3]Scientific theories are also distinguished from hypotheses, which are individual empirically testable conjectures, and scientific laws, which are descriptive accounts of how nature will behave under certain conditions

In other words, theory is the set of observations, concepts, laws, and bridging arguments that provide a framework for exploring a concept. The germ theory of disease, for example, is the based around the concept that many illnesses are caused by microbiological agents, such as bacteria or viruses. Gravitational theory incorporates our observational data regarding gravity, and also provides testable hypotheses concerning what gravity actually is and precisely what causes it to work.

An important aspect of theory is that it changes over time. Gravitational theory was once limited to discussions of how gravity worked to make large objects attract each other. It was descriptive, and sought to describe things such as the motions of the planets, as well as objects falling to Earth. Over time, however, it grew, and now incorporates Einstein's general relativity, elements of particle physics, and so on. It began with observations of objects on Earth as well as the movement of objects through the sky. As more information was gathered, observations refined, and other physics questions probed and discoveries made, more and more information was added to gravitational theory. It grew from being descriptive (telling us how things behaved) to being predictive (telling us how they should behave under different conditions), and is increasingly explanatory (telling us not only how things have been observed to behave, and how we should anticipate them to behave, but also why they behave that way - what is gravity, exactly, anyway?).

All legitimately scientific fields build theory in this way: phenomenon are observed, the way in which they occur is more closely scrutinized and data gathered, the new data allows predictions to be made (that is, allows you to formulate hypotheses), which in turn allows you to further refine observations, ideas, and explanations. Theory allows you to keep track of the various parts of a field of study, keep them coherent, and keep them from getting lost or confused. Without theory, any attempt at research is dead in the water.

Within paranormal research, there is very little in the way of theory-building. This is due, in part, to the fact that there is little in the way of coherent data gathering. All of the ghost hunters running around with all of the infrared cameras and EMF meters available isn't going to produce anything worthwhile if there isn't some sort of structure to the matter. Why are EMF meters used? Why are infrared thermometers used? What are you really capturing on your digital voice recorder? Who knows? There's no reason to use any of this equipment, outside of "well, it's what those guys on TV do!" or "it's what the Shadowlands website says investigators should do."

Consider that physicists don't just run around with whatever pieces of equipment they can come up with and declare that their readings are indicative of, say, proton decay. No, they work out what a proton actually is based on a variety of different lines of evidence, how it's structured, and what the necessary results of its decay would be. THEN they use specific pieces of equipment that detect the particular things for which they are searching to see if their basic hypothesis is correct. Similarly, if you wish to do real, legitimate paranormal research, you must first choose the phenomenon that you wish to look into, then you must start collecting basic data, then you form research questions based on those observations, and then, and only then, do you start to work out which specialized tools are appropriate for what you are trying to discover.

So, if the paranormal phenomenon that you are interested in is ghosts (my own go-to, as shown by the fact that I have essentially geared this entire discussion towards it), you must first determine if there is even a phenomenon to be studied by collecting information from both accounts of alleged hauntings and from research on related fields - and you have to be very, very cautious in accounting for as many potential fields as possible. In the case of allegedly haunted places, you are looking at claims based on perceptions and people's memories of events, so you have to make sure that you are accounting for current work in the fields of perception and memory. Once you have used these fields to analyze the information that you have, you look for anomalies. You then set about trying to make some sort of sense of these anomalies - is there a pattern to them? Can they be explained by known phenomenon (for example, most "shadow people" sightings can be easily explained by a knowledge of how the eyes function)? If they can not be explained cleanly by known phenomenon, is there a known phenomenon that kind-of fits it, and if so, is the observation in question better explained by altering the explanations of the known phenomenon in a reasonable way (say, by appealing to other known phenomenon that may influence the first), or is it really something new? If it is something new, you once again gather information, looking for patterns, and seeing if there is anything that connects the data together. Over time, you will start to see links, you will start to piece things together. But it takes a long time, and it take alot of work, and it is something that is never going to be achieved by running around old houses using whatever random piece of equipment is in vogue with the ghost hunters this year. And, importantly, if you do this, while you may discover something new and interesting, if you are doing real research, then you absolutely must be open to the fact that you may find that exotic-seeming events may in fact be best explained through mundane phenomenon. If you discover that ghost sightings are best explained by neurology, or bad reactions to certain chemicals, or pet allergies...well, then, that is what you discovered, and a real researcher accepts this.

Rather than this, however, the current fields of paranormal investigation in general, and ghost hunting in particular, is a weird, cobbled-together Frankenstein's monster of unsubstantiated claims, faddish devotion to particular tools, and concepts borrowed from fantasy stories dressed up to sound scientific (psychokinetic energies, quantum energies leading to psychic phenomenon, inter-dimensional beings, etc.), but always essentially being assertions or suppositions without evidential backing, or even a real line of logic leading to them.

But it was not always this way. During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, real researchers began to look into questions regarding whether or not there is something more to us than our living bodies, whether or not there are things such as psychic powers, and whether reports of hauntings indicate and actual paranormal phenomenon or were simply quirks of human perception.

This ended for a number of reasons - some social, but many scientific. Initial tests on precognition and clairvoyance, for example, often seemed to show something, only to have later results demonstrate a regression to the mean, indicating that it was random chance at work. In other realms of paranromal research, investigation often revealed fraud or simple mistakes. Over time, without clear, favorable results, enthusiasm fizzled. After a time, the only people willing to engage in this work were the people who were perfectly willing to ignore negative results, and to focus instead on what looked like positive results when taken out of the broader context of the total results.

In other words, most of the people who stayed in the game were unwilling to follow where their results led, and would instead falsify or ignore data. In that sort of environment, it didn't take long for every claim to be considered at least viable, no matter how absurd. And so it is that we have paranormal researchers yammering on about "stone tapes" and "quantum potentiation leading to life after death" and "everyone having psychic abilities" despite the fact that none of these claims have been demonstrated, and many (basically, any claim involving the words "quantum" or "dimension") being so divorced from the actual, legitimate scientific uses of the key words that they are, literally, gibberish.

So, if you really want to do real paranormal research, this needs to change. There needs to be a concerted and honest effort to build up theory. Data needs to be recorded honestly and cleanly, negative results need to be acknowledged as being just as valuable as positive results, and you have to abandon all great edifices of pseudo-scientific gobbly-gook and start from basics.

And understand - when you approach professional scientific researchers, you will likely have to fight back their preconceptions about what you are doing. It's not that they are "closed-minded fools", it's that they have encountered many would-be paranormal investigators in the past, and none of them have ever been willing to do the hard work of real research, and have instead insisted that unsupported assertions be taken as fact, that an ignorance of data gathering methods was somehow superior to a clear and thought-out research methodology, and that data should be accepted only when it is favorable. In short, they will have crossed paths with people who are closed-minded and not willing to hear constructive criticism, and then been accused of being that themselves (I have encountered this myself, as has every researcher that I know). It may not be fair for them to view you with the cynicism that decades of this have earned, but it is human nature, and you have to be ready for it.

Also, understand, criticism is an important part of real research. Whenever I present results, I expect to be criticized, because there will always be something that I didn't think of but that should have been considered, or some piece of data of which I was unaware, or some other way to think of the results that never occurred to me. If you spend time reading the work of various paranormal investigators, you will hear that the "mainstream" scientist are criticizing them out of fear, or loathing, or a desire to "shut out undesired voices." Bullshit. Criticism is an important part of science. We criticize each other's work, because that is how we keep ourselves honest, and how we ensure that the best ideas, explanations, and data will eventually rise to the top (admittedly, sometimes it takes a while, but it gets there eventually). If you are being criticized, it means that you are being treated like a scientist, not that you are being shut down.

It will be difficult, it often won't be fun. But if you are serious about being a researcher/investigator, and not just being some goofy person who runs about with equipment that they don't actually understand, then you absolutely have to do this. And if you do this, then any positive results that you may get will be meaningful, and will be real contributions. If you don't do this, then your work will continue to be pseudo-science at best.

Good luck. P.S., if you are reading this and insisting that paranormal research has developed good, solid, theory, then I would point out that such theory regarding the sorts of things implied would allow for working applications of the concepts and powers studied. To that end, I will simply point you to this:

Thursday, July 19, 2012

So, You Want to be a Paranormal Investigator, Part 2

It's been a little while since I posted part 1 of this, but here I am with Part 2 (edit to add: part 3 is here). A quick re-iteration: there are many people who engage in activities that could be labelled "ghost hunting" or "paranormal investigations." This set of entries is directed at the sub-set of them who are genuinely interested in trying to do good, robust work, and not those who simply want to hang out in creepy places (which, it must be said, is something that I enjoy doing, so I see nothing wrong with it). So, here we go...

In the last entry in this series, I discussed the problems inherent in basic data gathering. Although I focused on eye-witness testimony, and specifically all that is wrong with it, the basic concepts (know what type of data you are collecting, what [if anything] it actually means, and why you are collecting it) apply to any situation in which you are attempting to gather information.

So, the last entry focused on some of the basic ways to think your way through data gathering, this one is aimed at saving you time and money by looking at the different tools of the trade. I am going to be focused on actual tools that measure actual things - not on the use of "psychic devices" ranging from a medium's impressions to dowsing rods (which certainly have their own problems, but other have explained the issues there more clearly than I ever could). I will briefly discuss some of the more "exotic" tools amongst the ghost-hunter's cache, but will spend a bit more time on two types of equipment that I have more direct personal knowledge of: cameras and audio equipment.

Now, many a ghost-hunting enthusiast will say "ha! Well, this guy admits that his experience with this equipment is limited, so why should you listen to him and not us, us who use this equipment all the time?" Simple: Unlike them, I actually bothered to read up on what the equipment actually does and does not do, and while my direct experience is limited, I have been able to find enough to figure out that they are either lying or else know even less than I do about these devices.

So, for starters, here's a run-down of some of the more common equipment, what it gets used for, and what it actually does (Much of this information is well-summarized here, for the curious):

For starters, the ghost hunters seem to have a love affair with everything infra-red, which is odd. Infra-red devices read heat signatures. That's it. They do different things with these signatures (create images, measure temperatures, etc.), but their purpose is, simply to read heat signatures. What's more, each type of infra-red device reads heat signatures in a specific way, and usually (though I can't swear that this is always the case), they read SURFACE heat signatures. So, for example, an infra-red thermometer reads the temperature of a surface - not the air, not gases, not ectoplasm, but a surface. So, if you point an infrared thermometer through a room, you will get the temperature of whatever object happens to be on the other side oh the room (most likely the wall), but not something insubstantial, such as gasses, smoke, or a ghost. What's more, depending on what the object that you hit is made of, and what is connected to it, you may get radical-seeming variations from fairly common things. Infra-red motion detectors do a similar thing, detecting either major changes in temperature or the movement of objects with heat signatures different from whatever the background field is. Even if one is claiming that there is a "cold spot", it would need to be of sufficient temperature difference and size to trigger the motion detector.

Also, there tends to be a bit of an inconsistency with how these objects are used by ersatz investigators - I have seen shows, and had conversations with people, wherein images from infrared camera showing warm, human-shaped areas were held up as evidence of ghosts, while "cold spots" were also used simultaneously. So what is it? Is the ghost cold or warm? The fact that both tend to get used depending on what the equipment is picking up indicates that these people are detecting randomness, not ghosts - in any sort of field of measurement, there will be natural "clumpings" of readings due to basic random distribution (remember, random does not mean "evenly distributed", it means "without pattern", and "clumps" will appear whenever a pattern is lacking). Whenever you see these clumps, they can seem striking, if you don't understand the nature of random distribution (one thing I have learned about ghost hunters - they are, to a person - very, very bad at understanding statistics). So, finding areas that appear hot or cold with an infrared device is not really useful information unless you can demonstrate a reason for it to be a different temperature (the common trope of "we can't explain these readings, therefore- GHOST!" grows out of a basic mis-understanding of how this works - there is always the possibility of seeming anomalies in randomness, the odd readings only mean something if you have good reason to expect them to be something other than what they actually are - and area that remains cold after being hit with a blow-torch, for example).

Anyway, unlike some other critics of paranormal investigation, I will not say that infrared equipment is useless. I will, however, say that it is only useful if you have a clear reason to be using it, and you have a sufficient understanding of both how the equipment works and of the environment in which you are deploying it to be able to know with some degree of reliability whether or not you should be getting one set of reading and not another - and knowing that tends to require alot of background knowledge of both the place where you are, and of the basic engineering that went into building it and selecting the materials to build it. If you haven't done this minimal research, then your readings are essentially meaningless.

Similarly, electromagnetic field meters are often abused in the name of parapsychology. What an EMF meter does is measure the electromagnetic field. Electromagnetic fields are all around us - the Earth generates a giant one, and out bodies generate them as well, as do all electronics. These tools are useful in the hands of people who work with electrical equipment for a living, but tend not to produce meaningful results in the hands of anyone else. Why? Simple: there are many possible sources for EMFs, and someone who is accustomed to dealing with them will have an idea of what EMFs are anomalous, and which are to be expected. Moreover, when they find an anomalous one, someone with a background in electrical work is going to have an idea of what to look for as regards its source*. Moreover, the readings that one gets with an EMF meter depend in large part in the specifics of how one uses it. Many commercially available meters require multiple readings to be taken in a few different ways in order to find anything meaningful (so, someone walking into a room, taking one reading, and announcing that they have found something is a sign that the person in question hasn't a clue as to how to use their equipment). Similarly, the way one handles the meter may create anomalous readings: for example, my fiance and I once did a ghost walk during which we were all handed EMF meters, and she and I quickly discovered that we could make these particular models spike by flicking our wrists slightly while holding them - doing little to the electromagnetic field, but screwing with the sensors - it was fun watching the other tour members try to figure out why the ghosts wanted to play with her and I, and not any of them.

Similarly, people tend to like to use ion detectors and Geiger counters (although the Geiger counters are usually given another name). Ion detectors detect ions, atoms in which the total number of electrons are not equal tot the total number of protons and therefore have an electrical charge (positive or negative). Ions are both naturally occurring and can be created by a variety of different pieces of equipment. Geiger counters identify ionizing radiation from nuclear decay (alpha particles, beta particles or gamma rays), which, again, can be (in fact, usually is) naturally occurring, or can be the result of human activity. As with EMF fields and heat signatures, readings on these pieces of equipment are essentially meaningless unless you have a good reason to expect one type of reading over another.

In all of these cases, the infrared devices, the EMF detectors, the Geiger counters, and the ion detectors, the devices are not measuring something mystical, something weird, or something abnormal. They are not measuring paranormal energy, ghosts, or the Force. They are measuring properties that exist in the world, all around us, at all times. And all of them can only produce meaningful measurements if you know what should and/or should not be in a given location, which requires a whole heaping load of background research. Hell, in the case of things such as radiation and ions, a basic knowledge of local geology and weather is necessary to know what should or should not be present, and I rarely see a paranormal researcher consult a geology or meteorology textbook.

Okay, so now onto the items with which I have a bit more direct experience and a bit more to say.

While in college, I trained to be a radio DJ, but found that I had a much greater affinity for the recording and manipulation of audio than for the on-air hijinks that accompanied DJ-dom. I became pretty good at making the various audio devices to which I had access make all manner of weird sounds, manipulate signals in odd ways, and create audio effects unintended by the equipment's manufacturers. What's more, I learned of the many ways that audio equipment can pick up unexpected noise, and I learned that following a basic train of cause-and-effect, I could invariably find the source of the sound (which, often, was very different from what it initially sounded like on the recording). Now, mind you, I could track down the sources in a controlled studio environment - if the same sorts of things had occurred with a tape recorder out on the town, I'd have had a much harder time tracking down the source - it likely would often be impossible - but my experience in the studio had taught me that unlikely sources can create odd noise and effects in recordings.

Most commercially available audio equipment is different from the professional-grade stuio equipment in that it is usually more compact, and gives the operator less control - but it has all of the same basic parts and features, it just either pre-sets them to "typical" conditions, or else automates them into a few pre-sets. The point is, this equipment has pretty much the same ability to create anomalous sounds as the studio equipment that I used, but fewer ways for the operator to minimize interference or alter the sound produced to create a cleaner recording. What's more, outside of a controlled studio environment, things such as tape recorders picking up faint radio signals, as well as the re-use of old tapes creating "bleed through" is common.

Digital recorders avoid some problems (such as bleed through), but still have some of the same issues, and several new ones unique to digital audio.

To make matters worse, most enthusiasts of electronic voice phenomenon (EVP - the alleged voices of spirits captured on electronic equipment) advocate the use of white noise int he background when you make recordings. This is dumb. Dumb, stupid, foolish, and asinine. As you may recall from Part 1, the human brain looks for patterns in randomness, and in laboratory experiments it has been shown to be very, very common for people to swear that they have heard human voices saying specific, coherent things in randomly generated noise. So, if you create white noise and then sit and listen to it for voices, you are very likely to hear voices whether or not there is anything there.

So, when someone plays spooky noises that they recorded at the local cemetery, it probably goes without saying that I am singularly unimpressed. Even when they are sure that they hear a human voice answering questions, it is really, really unimpressive.

Now, am I not saying that audio equipment is useless. If you can routinely replicate certain types of phenomenon, and you are able to successfully rule out all common sources of interference, then you may have something. Now, what you have may be an uncommon problem with your equipment, or it may be something truly strange, and you will have to find different ways to further explore it, but you might (and note, I say "might" not "are") be on to something. In a more pedestrian sense, audio equipment, especially a good, simple tape recorder or digital voice recorder, is an excellent way to take quick, on-the-fly notes to help you out later. These things are useful pieces of equipment for any researcher, but as with everything else discussed here, you have to understand what they are and how they work, and how your brain interprets sound in order to get any real use out of them.

And now, onto cameras. I am a hobbyist photographer and have been for many years, so while I am not a professional photographer, I do know a thing or two about the subject. And when I see photographic "evidence" of hauntings, I am consistently underwhelmed.

First off, there's the fact that many of the things that are currently held up as evidence of ghosts - streaks, "orbs", etc. - are actually pretty well understood properties of how cameras function. A camera operates by bringing light in, and turning that light into an image, either on a photographic paper or through electronic sensors. Anything that reflects light will effect the image, and as cameras bring in light in a manner a bit different than how the human eye does, this means that objects may appear on film or in digital images that are not visible to the naked eye. Small objects that can reflect light (raindrops, motes of dust, insects, etc.) tend to reflect it in a spherical pattern that is not visible to the human eye, but does show up on camera. If the object is caught in a particular way or is moving quickly enough, this may show up as a "streak" rather than a sphere. Likewise, small light sources, maybe dim enough to not be noticeable to the naked eye, may show up on film as streaks if the camera or the object emitting the light is moving, even slightly, when the shot is taken. This is especially true in low-light conditions. Now, some people will say "well, this orb is translucent, that one is solid, therefore we know that this one is an artifact of light, BUT the other is a ghost!" Nope, sorry, both are artifacts of light, and anyone who tells you different is either completely ignorant of photography, or is lying to you.

Indeed, it is a sad fact that the reason why we have these obvious artifacts being held up as ghostly images is because most of us are familiar enough with special effects that we will no longer uncritically accept a modified image. As a result, those who wish to capture ghosts on film have tried to find ways to use unmodified images to support their claims. The problem there, of course, being that, to anyone who knows the ins-and-outs of camera functionality, these images are pretty clearly mundane. The fact that there are some photographers who are only to ready to jump on the spooky bandwagon (usually to make money off of selling either their services or their photographs) doesn't change the fact that these really are pretty damn mundane.

On a related note, it is common for people to take other types of photographs from other people as evidence of ghostly activity. Typically, the line goes something like this: a photograph appears to show something strange, it was taken to a photography expert who states that there are no signs of tampering with the image, and therefore the image really does show something strange!

Leaving aside the images created via pariedolia, there is another problem here. All of the images below are analogous to types used as evidence for paranormal phenomenon. None of them have been tampered with, and therefore would show no signs of tampering if examined:

Every one of them shows a vague human outline, or a human form that is insubstantial, or a face that seems somehow wrong. In some of them you will have to look closely, but these sorts of ghostly images are present in every one of them. Several have strange streaks of light or "orbs".

Those human shapes in the ghostly images are myself, and my friends Robin, Michael, and Robert. None of the images were created using photo manipulation software, studio editing, or any other form of image manipulation. In other words, not a single one was tampered with, and none of them would show signs of tampering if examined.

Which doesn't mean that there was no trickery involved. I used a variety of techniques to create these images: pinhole apertures, slow shutter speeds in low-light conditions, and a mix of digital and film cameras, utilizing properties unique to each of them. In some of the images, I intentionally used non-optimal settings (making the exposure to bright or too dark, putting the image slightly out-of-focus, etc.) to make the image look just slightly not-right before inserting the spooky element (this serves to prep the viewer to see the image as spookier than it really is). I used cameras with light leakage, or used flashes, to create the streaks and orbs. I created the images intentionally, knowing full well what I was doing, and what I was going to get when I was done. So, just because a photo has not been edited or altered doesn't mean that it is real, and this should be kept in mind whenever you are presented with a photograph as evidence.

But this also brings us to another issue: that, like the audio equipment, lower-end cameras (especially digital point-and-click cameras, but also many non-professional film cameras) have the same parts as higher-end cameras (lenses, film or sensors, apertures, etc.), but generally automate those parts or have them at pre-sets, limiting the ability for the user to manipulate them in order to cut out interference, creating numerous anomalies that may seem odd or even spooky to someone not familiar with how to intentionally create the same sorts of images. Moreover, an unwary user of a film camera is likely to end up with double-exposures, which can result in "a person who wasn't there appearing in the image!", and most people using these cameras on ghost hunts do not keep accurate photo logs in order to recall the precise conditions under which images were created.

Like audio equipment, cameras are useful tools. They can allow you to document conditions, act as a supplement to your field notes, and there is a small but real chance that you may even catch something in the image that might prompt further investigation.

While the IF devices and EMF meters, etc. are probably best left at home, cameras and audio equipment are legitimately useful, and should accompany someone who is trying to do real investigation. But you should always be aware of the limits of your equipment, the nature of your equipment, and of the fact that many of the things taken as evidence of ghosts are, in fact, easily explainable by someone who knows what the equipment is and how it works. So, bear all of this in mind when using it.

Okay, the next part, which I hope to post in the not-too-distant future, will focus on the basica problems inherent in the lack of theory and testable hypotheses in paranormal research, and what you can do to make things better.

* Fun fact: on occasion, a television show will bring someone in who is said to have the correct background to make sense of EMF readings. Assuming that they do (and given the way that paranormal television shows often play fast-and-loose with the qualifications of people who I have actually know the background of, I have little hope that they get anyone else's qualifications correct), the devices are almost always shown being used in a manner inconsistent with what is needed to get reliable readings. So, even in these cases, the devices are being mis-used.

In the last entry in this series, I discussed the problems inherent in basic data gathering. Although I focused on eye-witness testimony, and specifically all that is wrong with it, the basic concepts (know what type of data you are collecting, what [if anything] it actually means, and why you are collecting it) apply to any situation in which you are attempting to gather information.

So, the last entry focused on some of the basic ways to think your way through data gathering, this one is aimed at saving you time and money by looking at the different tools of the trade. I am going to be focused on actual tools that measure actual things - not on the use of "psychic devices" ranging from a medium's impressions to dowsing rods (which certainly have their own problems, but other have explained the issues there more clearly than I ever could). I will briefly discuss some of the more "exotic" tools amongst the ghost-hunter's cache, but will spend a bit more time on two types of equipment that I have more direct personal knowledge of: cameras and audio equipment.

Now, many a ghost-hunting enthusiast will say "ha! Well, this guy admits that his experience with this equipment is limited, so why should you listen to him and not us, us who use this equipment all the time?" Simple: Unlike them, I actually bothered to read up on what the equipment actually does and does not do, and while my direct experience is limited, I have been able to find enough to figure out that they are either lying or else know even less than I do about these devices.

So, for starters, here's a run-down of some of the more common equipment, what it gets used for, and what it actually does (Much of this information is well-summarized here, for the curious):

For starters, the ghost hunters seem to have a love affair with everything infra-red, which is odd. Infra-red devices read heat signatures. That's it. They do different things with these signatures (create images, measure temperatures, etc.), but their purpose is, simply to read heat signatures. What's more, each type of infra-red device reads heat signatures in a specific way, and usually (though I can't swear that this is always the case), they read SURFACE heat signatures. So, for example, an infra-red thermometer reads the temperature of a surface - not the air, not gases, not ectoplasm, but a surface. So, if you point an infrared thermometer through a room, you will get the temperature of whatever object happens to be on the other side oh the room (most likely the wall), but not something insubstantial, such as gasses, smoke, or a ghost. What's more, depending on what the object that you hit is made of, and what is connected to it, you may get radical-seeming variations from fairly common things. Infra-red motion detectors do a similar thing, detecting either major changes in temperature or the movement of objects with heat signatures different from whatever the background field is. Even if one is claiming that there is a "cold spot", it would need to be of sufficient temperature difference and size to trigger the motion detector.

Also, there tends to be a bit of an inconsistency with how these objects are used by ersatz investigators - I have seen shows, and had conversations with people, wherein images from infrared camera showing warm, human-shaped areas were held up as evidence of ghosts, while "cold spots" were also used simultaneously. So what is it? Is the ghost cold or warm? The fact that both tend to get used depending on what the equipment is picking up indicates that these people are detecting randomness, not ghosts - in any sort of field of measurement, there will be natural "clumpings" of readings due to basic random distribution (remember, random does not mean "evenly distributed", it means "without pattern", and "clumps" will appear whenever a pattern is lacking). Whenever you see these clumps, they can seem striking, if you don't understand the nature of random distribution (one thing I have learned about ghost hunters - they are, to a person - very, very bad at understanding statistics). So, finding areas that appear hot or cold with an infrared device is not really useful information unless you can demonstrate a reason for it to be a different temperature (the common trope of "we can't explain these readings, therefore- GHOST!" grows out of a basic mis-understanding of how this works - there is always the possibility of seeming anomalies in randomness, the odd readings only mean something if you have good reason to expect them to be something other than what they actually are - and area that remains cold after being hit with a blow-torch, for example).

Anyway, unlike some other critics of paranormal investigation, I will not say that infrared equipment is useless. I will, however, say that it is only useful if you have a clear reason to be using it, and you have a sufficient understanding of both how the equipment works and of the environment in which you are deploying it to be able to know with some degree of reliability whether or not you should be getting one set of reading and not another - and knowing that tends to require alot of background knowledge of both the place where you are, and of the basic engineering that went into building it and selecting the materials to build it. If you haven't done this minimal research, then your readings are essentially meaningless.

Similarly, electromagnetic field meters are often abused in the name of parapsychology. What an EMF meter does is measure the electromagnetic field. Electromagnetic fields are all around us - the Earth generates a giant one, and out bodies generate them as well, as do all electronics. These tools are useful in the hands of people who work with electrical equipment for a living, but tend not to produce meaningful results in the hands of anyone else. Why? Simple: there are many possible sources for EMFs, and someone who is accustomed to dealing with them will have an idea of what EMFs are anomalous, and which are to be expected. Moreover, when they find an anomalous one, someone with a background in electrical work is going to have an idea of what to look for as regards its source*. Moreover, the readings that one gets with an EMF meter depend in large part in the specifics of how one uses it. Many commercially available meters require multiple readings to be taken in a few different ways in order to find anything meaningful (so, someone walking into a room, taking one reading, and announcing that they have found something is a sign that the person in question hasn't a clue as to how to use their equipment). Similarly, the way one handles the meter may create anomalous readings: for example, my fiance and I once did a ghost walk during which we were all handed EMF meters, and she and I quickly discovered that we could make these particular models spike by flicking our wrists slightly while holding them - doing little to the electromagnetic field, but screwing with the sensors - it was fun watching the other tour members try to figure out why the ghosts wanted to play with her and I, and not any of them.

Similarly, people tend to like to use ion detectors and Geiger counters (although the Geiger counters are usually given another name). Ion detectors detect ions, atoms in which the total number of electrons are not equal tot the total number of protons and therefore have an electrical charge (positive or negative). Ions are both naturally occurring and can be created by a variety of different pieces of equipment. Geiger counters identify ionizing radiation from nuclear decay (alpha particles, beta particles or gamma rays), which, again, can be (in fact, usually is) naturally occurring, or can be the result of human activity. As with EMF fields and heat signatures, readings on these pieces of equipment are essentially meaningless unless you have a good reason to expect one type of reading over another.

In all of these cases, the infrared devices, the EMF detectors, the Geiger counters, and the ion detectors, the devices are not measuring something mystical, something weird, or something abnormal. They are not measuring paranormal energy, ghosts, or the Force. They are measuring properties that exist in the world, all around us, at all times. And all of them can only produce meaningful measurements if you know what should and/or should not be in a given location, which requires a whole heaping load of background research. Hell, in the case of things such as radiation and ions, a basic knowledge of local geology and weather is necessary to know what should or should not be present, and I rarely see a paranormal researcher consult a geology or meteorology textbook.

Okay, so now onto the items with which I have a bit more direct experience and a bit more to say.

While in college, I trained to be a radio DJ, but found that I had a much greater affinity for the recording and manipulation of audio than for the on-air hijinks that accompanied DJ-dom. I became pretty good at making the various audio devices to which I had access make all manner of weird sounds, manipulate signals in odd ways, and create audio effects unintended by the equipment's manufacturers. What's more, I learned of the many ways that audio equipment can pick up unexpected noise, and I learned that following a basic train of cause-and-effect, I could invariably find the source of the sound (which, often, was very different from what it initially sounded like on the recording). Now, mind you, I could track down the sources in a controlled studio environment - if the same sorts of things had occurred with a tape recorder out on the town, I'd have had a much harder time tracking down the source - it likely would often be impossible - but my experience in the studio had taught me that unlikely sources can create odd noise and effects in recordings.

Most commercially available audio equipment is different from the professional-grade stuio equipment in that it is usually more compact, and gives the operator less control - but it has all of the same basic parts and features, it just either pre-sets them to "typical" conditions, or else automates them into a few pre-sets. The point is, this equipment has pretty much the same ability to create anomalous sounds as the studio equipment that I used, but fewer ways for the operator to minimize interference or alter the sound produced to create a cleaner recording. What's more, outside of a controlled studio environment, things such as tape recorders picking up faint radio signals, as well as the re-use of old tapes creating "bleed through" is common.

Digital recorders avoid some problems (such as bleed through), but still have some of the same issues, and several new ones unique to digital audio.

To make matters worse, most enthusiasts of electronic voice phenomenon (EVP - the alleged voices of spirits captured on electronic equipment) advocate the use of white noise int he background when you make recordings. This is dumb. Dumb, stupid, foolish, and asinine. As you may recall from Part 1, the human brain looks for patterns in randomness, and in laboratory experiments it has been shown to be very, very common for people to swear that they have heard human voices saying specific, coherent things in randomly generated noise. So, if you create white noise and then sit and listen to it for voices, you are very likely to hear voices whether or not there is anything there.

So, when someone plays spooky noises that they recorded at the local cemetery, it probably goes without saying that I am singularly unimpressed. Even when they are sure that they hear a human voice answering questions, it is really, really unimpressive.

Now, am I not saying that audio equipment is useless. If you can routinely replicate certain types of phenomenon, and you are able to successfully rule out all common sources of interference, then you may have something. Now, what you have may be an uncommon problem with your equipment, or it may be something truly strange, and you will have to find different ways to further explore it, but you might (and note, I say "might" not "are") be on to something. In a more pedestrian sense, audio equipment, especially a good, simple tape recorder or digital voice recorder, is an excellent way to take quick, on-the-fly notes to help you out later. These things are useful pieces of equipment for any researcher, but as with everything else discussed here, you have to understand what they are and how they work, and how your brain interprets sound in order to get any real use out of them.

And now, onto cameras. I am a hobbyist photographer and have been for many years, so while I am not a professional photographer, I do know a thing or two about the subject. And when I see photographic "evidence" of hauntings, I am consistently underwhelmed.

First off, there's the fact that many of the things that are currently held up as evidence of ghosts - streaks, "orbs", etc. - are actually pretty well understood properties of how cameras function. A camera operates by bringing light in, and turning that light into an image, either on a photographic paper or through electronic sensors. Anything that reflects light will effect the image, and as cameras bring in light in a manner a bit different than how the human eye does, this means that objects may appear on film or in digital images that are not visible to the naked eye. Small objects that can reflect light (raindrops, motes of dust, insects, etc.) tend to reflect it in a spherical pattern that is not visible to the human eye, but does show up on camera. If the object is caught in a particular way or is moving quickly enough, this may show up as a "streak" rather than a sphere. Likewise, small light sources, maybe dim enough to not be noticeable to the naked eye, may show up on film as streaks if the camera or the object emitting the light is moving, even slightly, when the shot is taken. This is especially true in low-light conditions. Now, some people will say "well, this orb is translucent, that one is solid, therefore we know that this one is an artifact of light, BUT the other is a ghost!" Nope, sorry, both are artifacts of light, and anyone who tells you different is either completely ignorant of photography, or is lying to you.

Indeed, it is a sad fact that the reason why we have these obvious artifacts being held up as ghostly images is because most of us are familiar enough with special effects that we will no longer uncritically accept a modified image. As a result, those who wish to capture ghosts on film have tried to find ways to use unmodified images to support their claims. The problem there, of course, being that, to anyone who knows the ins-and-outs of camera functionality, these images are pretty clearly mundane. The fact that there are some photographers who are only to ready to jump on the spooky bandwagon (usually to make money off of selling either their services or their photographs) doesn't change the fact that these really are pretty damn mundane.

On a related note, it is common for people to take other types of photographs from other people as evidence of ghostly activity. Typically, the line goes something like this: a photograph appears to show something strange, it was taken to a photography expert who states that there are no signs of tampering with the image, and therefore the image really does show something strange!

Leaving aside the images created via pariedolia, there is another problem here. All of the images below are analogous to types used as evidence for paranormal phenomenon. None of them have been tampered with, and therefore would show no signs of tampering if examined:

Every one of them shows a vague human outline, or a human form that is insubstantial, or a face that seems somehow wrong. In some of them you will have to look closely, but these sorts of ghostly images are present in every one of them. Several have strange streaks of light or "orbs".

Those human shapes in the ghostly images are myself, and my friends Robin, Michael, and Robert. None of the images were created using photo manipulation software, studio editing, or any other form of image manipulation. In other words, not a single one was tampered with, and none of them would show signs of tampering if examined.

Which doesn't mean that there was no trickery involved. I used a variety of techniques to create these images: pinhole apertures, slow shutter speeds in low-light conditions, and a mix of digital and film cameras, utilizing properties unique to each of them. In some of the images, I intentionally used non-optimal settings (making the exposure to bright or too dark, putting the image slightly out-of-focus, etc.) to make the image look just slightly not-right before inserting the spooky element (this serves to prep the viewer to see the image as spookier than it really is). I used cameras with light leakage, or used flashes, to create the streaks and orbs. I created the images intentionally, knowing full well what I was doing, and what I was going to get when I was done. So, just because a photo has not been edited or altered doesn't mean that it is real, and this should be kept in mind whenever you are presented with a photograph as evidence.